I

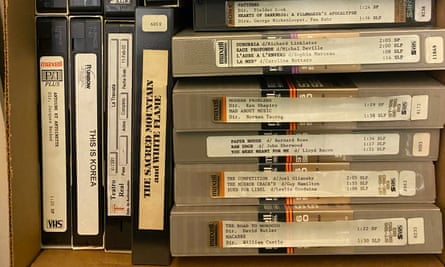

The archives of Rare and Distinctive Collections at the University of Colorado Boulder’s main library are located in the basement of an 85-year-old stone building designed in the style of a rural Italian fortress. The shelves here are lined with a vast collection of yellowed books, historical maps, and medieval manuscripts. Hidden within these rows of items is an unexpected treasure – Martin Scorsese’s personal collection. Scorsese, a renowned director and film preservationist, has quietly stored thousands of VHS tapes in over 50 storage boxes. These tapes contain films and television programs that he recorded directly from broadcast television, revealing his secret role as a prolific guerrilla archivist.

Before platforms like YouTube and Netflix existed, Scorsese took on the task of building his own comprehensive video collection. Each week, he would flip through TV Guide and make note of any films or shows that piqued his interest. A dedicated video archivist in his New York office would then record these televised programs from a central audiovisual setup consisting of multiple VCRs and monitors, often running round the clock. The tapes were carefully labeled, organized using a card system or computer, and stored for Scorsese’s personal viewing and research.

Containing over 4,400 unique titles, the Martin Scorsese VHS Tape Collection spans from the 1980s to the 2000s. This impressive collection includes a variety of genres such as feature films, documentaries, shorts, historical programs, and award shows. By browsing the online catalogue, one can find a diverse range of content, from European art films to a special episode of Live with Regis and Kathie Lee featuring Scorsese’s mother, Catherine, who was a regular guest in her son’s movies. As the archive continued to expand, Scorsese incorporated the videos into his filmmaking process, often using them as reference materials for the cast and crew during pre-production.

Please open the image in full-screen mode.

In a written interview, Scorsese explained that he tends to use this technique in most of his pictures. For the actors, the purpose is usually to convey a certain tone, mood, or emotional state that aligns with the world they are trying to bring to life. As for the crew members, the focus is often on using cuts, camera movements, and framing techniques to enhance specific points in the story. This is not about copying anything directly, but rather suggesting an approach to effectively telling the story.

The assortment is a tangible representation of Scorsese’s well-known diverse interest in visual media. In numerous occasions, Scorsese has discussed his childhood as an asthmatic in a home devoid of books, but was among the first on their street to obtain a television in 1948, when he was six years old. For young Marty, who wasn’t able to play outside as much as other children, the 16-inch screen of the black-and-white RCA Victor in the living room served as his connection to the outside world, and more importantly, his initial introduction to exceptional filmmaking.

On Friday nights, a station in New York would feature films from Italian Neorealism. He would often watch these movies with his family, who had immigrated from Sicily. He was particularly drawn to the work of Roberto Rossellini, which he later explored in his 1999 documentary, My Voyage to Italy. In the late 1950s, Scorsese would tune in to Million Dollar Movie, a program that screened the same film twice a day during weekdays and three times a day on weekends. This allowed him to closely study the craft of films like Citizen Kane, including camera movements, use of music, and special effects like slow motion. From grade school to his days at NYU, Scorsese would do his homework while watching muted TV images in front of him. Later on, he continued this habit in the editing room while working with his longtime editor, Thelma Schoonmaker. He has even admitted to feeling a sense of loneliness without the presence of a television.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

According to Paul Mougey, a former NYU film student who worked as Scorsese’s video archivist for four years in the late 1980s, Scorsese was always avidly observing, absorbing, and learning. In 1990, Scorsese established the non-profit organization, Film Foundation, which has successfully restored over 1,000 films. Mougey explains, “Marty’s goal was to obtain every movie ever made, and we documented them all. He believed that part of his duty as a preservationist was to build a remarkable library and make it available to his acquaintances.”

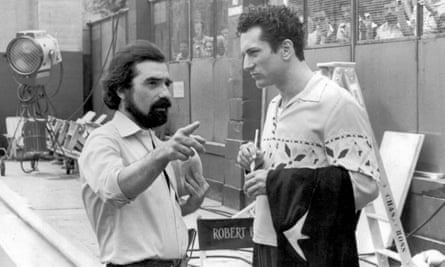

Mougey fondly recalls the day at Scorsese’s office, then located in New York’s historic Brill Building, when “Bobby” De Niro turned up in boat shoes to pick up a VHS tape containing a film Scorsese wanted him to see before they began shooting Goodfellas. “I just remember thinking he was such a relaxed dude. Very quiet, very polite, very nice,” says Mougey, who landed a cameo as Terrorized Waiter in the 1990 gangster classic. One of Mougey’s successors, Kent Jones, would rise from video archivist to regular Scorsese collaborator, including co-writing A Life of Jesus, which is slated to be Scorsese’s follow-up to last year’s Killers of the Flower Moon.

A few years ago, Scorsese began gradually giving away his VHS collection. With the widespread availability of high-quality DVDs and Blu-rays, as well as the popularity of streaming, much of the large tape collection had lost its value. Scorsese’s film archivists, Mark McElhatten and Gina Telaroli, who were friends with Erin Espelie, an associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, worked together to help the university obtain the collection. In 2021, the last boxes of tapes were delivered to Boulder from Scorsese’s Sikelia Productions office in Manhattan.

It may seem odd that Martin Scorsese’s collection is located at the University of Colorado Boulder. After all, the 81-year-old is widely known for his films depicting life in New York. He himself attended New York University and previously taught at their undergraduate film-making program. In 2021, NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts established the Martin Scorsese Institute of Global Cinematic Arts, which includes a production center and cinema studies department bearing his name. However, the Rare and Distinctive Collections in Boulder has established itself as a hub for studying the history of film and video, with valuable collections from experimental film-makers such as Stan Brackhage and Ken and Flo Jacobs.

“In an email, Espelie stated that Scorsese ultimately paid tribute to the experimental film origins of the University of Colorado Boulder and showed admiration for our focus on combining archival work with teaching. It is our aim, as the Department of Cinema Studies and Moving Image Arts, that the Scorsese VHS archive will be utilized by students, scholars, and community members for various purposes. These include further understanding how Scorsese incorporated the work of others into his filmmaking process, learning about his extensive viewing habits, and discovering the television programs and movies he often shared with his cast members. Additionally, the archive provides a valuable source for documenting the content that was available on television at the time.”

According to Espelie, the broadcast recordings consist of commercials, bumpers, and other supplemental elements that are just as intriguing as the intended main recordings. Due to the lack of backups in television at the time, these VHS tapes may be the only sources for these “interstitial” materials.

The top priority for the archivists at Rare and Distinct Collections is to preserve the Scorsese collection. As magnetic media ages, it deteriorates, with VHS tapes losing image quality after just 10 years. Many of Scorsese’s tapes are over 40 years old, making it crucial to digitize the entire archive, which is no small task. Converting a large number of analog recordings is a slow and tedious process. Currently, the university mandates that individuals requesting materials cover the cost of digitizing any tape that has not yet been converted.

After the collection becomes easily available, Tiel Lundy, an associate film professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, anticipates researchers will start performing comparative examinations, identifying what Scorsese was viewing at a specific period and how it may have influenced his subsequent creations. Lundy believes this could be an excellent opportunity for a book project.

Upon learning about the Scorsese collection, John Klacsmann, an archivist at Anthology Film Archives in New York, was immediately intrigued by the possibility that the director may have recorded some unique and rare footage. According to an email statement, Klacsmann believes that there could be hidden gems such as obscure or unreleased films, television broadcasts, and director’s cuts within the collection from the 1980s. He is especially curious about the viewing list that may have influenced Scorsese’s cinematic masterpieces like “The King of Comedy” and “The Last Temptation of Christ.”

Source: theguardian.com