T

The act of sharing stories is a form of being hospitable. Stories are a generous tradition that teaches us about the modern world. They are essential for our survival as humans and allow for a welcoming and understanding exchange between individuals. The stories we tell not only reflect us accurately, but they also bring us together in a shared experience. Stories promote inclusion and reject exclusion, showing that they are not just a tool for spreading a certain message.

Recent news in the UK reveals the continued mistreatment of refugees, highlighting the inhumanity of our country. For instance, if I am seeking asylum and living under the care of the Home Office, my death may go unnoticed and unreported to my family. Additionally, if I am a homeless person living on the streets of England, it is highly probable that I am a refugee who has been evicted from temporary housing provided by the Home Office. These issues were reported just last week.

The divisive language used by politicians in this country does not attempt to convey the true experiences of individuals, such as a 16-year-old boy making a perilous journey across the desert and ocean to reach a new continent, or the devastating loss caused by war, climate change, or political turmoil. Those who are forced to flee their homes due to religious, ethnic, or gender-based persecution are reduced to mere pawns in the political game, as politicians strip the term “refugee” of its original meaning – someone seeking safety from danger, difficulty, or persecution. Instead of addressing the plight of millions of displaced individuals, many of whom are escaping poverty, violence, and natural disasters, politicians are more focused on using their struggles to further their own divisive political agendas.

These four films cover a spectrum of emotions, from pressing to awe-inspiring, and explore the experiences of individuals whose lives are shaped by external factors. Each film delves into the personal stories with meticulous attention and empathy, bringing a deeper understanding to the complexities of each person’s journey.

–

All of these movies are incredible tales. Each one reveals a condemnation. Each one uncovers a hidden perspective, one that is often overlooked. Each one challenges our assumptions about bravery, heroism, tragedy, and the ability to persevere against extraordinary challenges. They each bring to light, with urgent importance, the true story not only of the present but of all humanity. Ali Smith.

Io Capitano, directed by Matteo Garrone

Show the image in full screen mode.

In July 2014, Fofana Amaro, a 15-year-old from West Africa, was coerced by human traffickers to pilot a migrant boat from Libya to Sicily with 250 passengers. Despite the obstacles, Amaro successfully completed the journey and proudly declared himself as the captain to the Italian coastguard upon their arrival. However, he was subsequently arrested and detained for accusations of human trafficking.

According to Italian director Matteo Garrone, his new film “Io Capitano” is based directly on the experiences of Amaro and two other migrants who risked their lives to travel from Africa to Europe. Despite being heroes for saving many lives, these migrants ultimately become victims of a system that vilifies them for seeking a better life. The film primarily follows the journey of Seydou and Moussa, two Senegalese protagonists, as they make the treacherous trek through the Sahara desert, often facing exploitation, imprisonment, and torture at the hands of private militias. This perilous land journey is lesser-known but just as dangerous as the sea crossing that follows.

Garrone explains to me during our phone conversation from Los Angeles, where he is promoting his film prior to the Oscars, that he wanted to portray the invisible aspect of the journey that is often overlooked by the media. He also aimed to humanize the individuals who become mere statistics along the way, a staggering 50,000 of whom have lost their lives within the past decade.

The two primary roles in the movie are portrayed by Seydou Sarr and Moustapha Fall, both being new to the acting scene and having no experience outside of Senegal. Sarr, known for his popular TikTok videos and Afropop music featured in the film’s soundtrack, surprises audiences with his performance as the more easily influenced character. Interestingly, he almost missed the opportunity to audition because he wanted to focus on playing soccer instead.

During filming, the director skillfully utilized the pair’s lack of experience by giving them pieces of the script each day. “Throughout most of the production, they were unaware of the full story or if they would successfully reach Europe,” he explains. “However, as they worked through the journey step by step, they developed as actors.”

To enhance the realism, numerous individuals featured in the film, such as those seen in the pivotal scenes of a busy boat crossing, were previous migrants. Some of them even assisted in writing the script and were present during filming to advise. “I would even say they co-directed certain scenes,” Garrone adds. “I was merely an observer and sometimes the initial viewer of what we brought to life.”

The movie starts in Dakar, where Moussa convinces his cousin Seydou that the only chance they have at achieving their dream of becoming famous pop singers is in Europe. Together, they make a plan to leave their small world of family and community, and seek protection from a local shaman before embarking on their journey. Soon, their innocence fades as they are forced onto a truck that carelessly drives through treacherous Saharan sand dunes. The driver ignores their pleas to stop, even when one of their group falls off the overcrowded vehicle. Director Garrone remarks, “They begin their journey as naive individuals, but quickly realize they are stuck in a dangerous trip from which there is no turning back.”

The filmmaker, renowned for the brutal underworld drama Gomorrah and a recent imaginative adaptation of Pinocchio, shares with me that Io Capitano merges elements from these two films. He depicts the new project as a “coming-of-age” tale that follows the traditional Homeric outline and portrays the protagonist’s transformation from naivety to gained wisdom.

The stark contrast between the harsh realities faced by the characters and the stunning visual imagery of moonlit deserts and expansive oceans is both dramatic and unexpected. One particularly daring scene features Seydou, heartbroken, envisioning rescuing a woman left to die in the desert by guiding her floating body to safety across the sand. According to Garonne, when the film was shown in Dakar, the audience responded with cheers and laughter.

“It is a means of expressing Seydou’s internal pain, while also showcasing his childlike purity and creativity. Despite his mature journey, the numerous experiences that inflict harm upon his soul will ultimately shape him into a grown man.”

Garrone emphasizes that Seydou remains morally upright despite being separated from his cousin, who is permanently injured from the cruelty inflicted upon him by his captors. Despite facing brutal and exploitative treatment, he maintains his innocence until the very end. Similar to Pinocchio, he is a naive young person searching for a place of happiness, only to realize too late that the world can be a harsh and violent place.

Io Capitano blends elements of harsh realism and thrilling escapades to tackle a timely and contentious topic. The filmmaker, Garonne, envisions the film being incorporated into educational curricula in both Europe and Africa, similar to how it has been embraced in Italy. Garonne notes that students can relate to protagonists Seydou and Moussa due to their shared age, interests, and love for music, as well as their common concerns for their families. The film aims to present a unique perspective on the ongoing crisis, in contrast to the often biased viewpoints propagated by conservative politicians and media outlets.

Although Io Capitano did not receive the Oscar for best international feature, it did earn Garrone the Silver Lion for best director and Sarr the best young actor award at the previous year’s Venice film festival. One can tell that Garrone takes the most pride in another, less glamorous recognition: his and Sarr’s visit with the pope, who screened the film at the Vatican shortly after its release in Italy. “He shared it with the cardinals and invited us for a one-hour audience,” explains Garrone. “He has always been supportive of migrants. In his eyes, they are heroes, not to be vilified.”

Io Capitano concludes with a sense of uncertainty as Seydou, the captain, finally spots land and his excitement spreads to his worn-out and cramped vessel. Despite the bittersweetness of this moment, it is clear that challenges and hardships still lay ahead for Seydou, his cousin, and his desperate passengers. Director Gianluca Garrone expresses his belief in the need for open borders with controlled measures and for providing aid to those who arrive. He also acknowledges, as shown in the film, that reaching a destination by sea is a heroic feat. In an interview with Sean O’Hagan, Garrone shares his motivations for creating this epic modern odyssey.

“Cinemas in the UK and Ireland will be showing films starting on 5 April.”

, was a top-rated Polish drama film.

“The top-rated Polish drama film, Green Border, was directed by Agnieszka Holland.”

Please enlarge the image to full-screen size.

Agnieszka Holland has extensively explored some of the most devastating moments in European history. As an experienced filmmaker from Poland, she has delved into the subject of the Holocaust in films like In Darkness, Europa Europa, and Angry Harvest, as well as highlighted the repressive regime of communism in her film To Kill a Priest. In her most recent work, the powerful and intense Green Border, Holland shifts her focus to the current refugee crisis in Europe, specifically at the border between Poland and Belarus. By using multiple perspectives and intertwining storylines, Green Border sheds light on this ongoing issue with a sense of urgency and palpable anger.

In recent times, individuals seeking asylum out of desperation were manipulated by the Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko and provoking the geopolitical crisis, which was further exacerbated by the Polish government. Lukashenko used propaganda to lure refugees into believing they would have a safe means of entering Europe at the border, but upon arrival, they were subjected to inhumane treatment and were bounced between the border authorities of both nations. Some lost their lives at the hands of these authorities, while others disappeared in the dangerous forests and swamps.

During a radio interview following the premiere of the film at the Venice film festival, Holland described the events as a “laboratory of absurd violence”. She also noted that this violence was concealed from the public due to the closed nature of the zone. Despite the severity of the situation, there was no media coverage, involvement from humanitarian or medical organizations, further isolating the victims.

“My colleagues and I determined that the best way to share this story would be through a fictional film, as creating a documentary proved to be unrealistic. The individuals involved had been silenced and it was our responsibility to give them a voice. We had to create a platform, not only for them but also for ourselves, to convey our emotions, understanding, and beliefs regarding the circumstances.”

According to Holland, the largest obstacle facing Europe at present is the migrant crisis. She believes that although a movie alone cannot alter the outcome of historical events, film holds a vital role in humanizing and putting a human face and voice to those who are migrants and refugees. Holland emphasizes the importance of seeing and understanding their experiences, struggles, decisions, families, and aspirations in order to avoid stereotypes and treat them as human beings.

Holland expected that the movie would stir controversy among specific groups in the Polish government and society due to its challenge of the carefully curated official narrative concerning the situation at the Polish-Belarusian border. However, she did not foresee the overwhelming backlash that ensued upon the film’s release in Poland last September. In an interview with Screen International, Holland described the negative response as a “tsunami of hate” that was organized by top authorities. The former Minister of Justice, Zbigniew Ziobro, even went as far as comparing the film to Nazi propaganda from World War II. Additionally, Poland’s President, Andrzej Duda, joined in by condemning the film’s audience as collaborators with the Nazis, despite not having seen the movie himself.

The country of Holland showed resistance, with their leader stating, “This occurred prior to the elections in Poland, where the conservative and nationalistic government saw an opportunity to gain support by targeting me and painting Poland as a besieged fortress under attack by an enemy force, with myself at the forefront. However, their efforts were excessive. Most people’s response was, ‘What are they even talking about?'”

The government’s anger actually had an unintended effect: “It increased awareness of the movie and also boosted our box office. And a movie like this needs backing.” – Wendy Ide

On June 21st, cinemas in the United Kingdom and Ireland will be open.

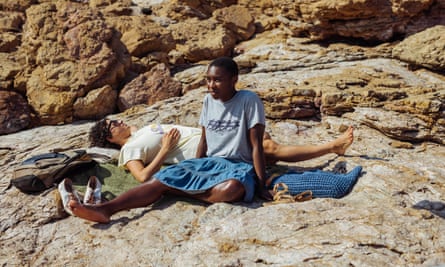

Drift, directed by Anthony Chen

Display the image in full screen mode.

Drift, the debut English-language film by Singaporean director Anthony Chen, sets itself apart from recent refugee-centered dramas through its intimate and focused approach, devoid of political commentary. The main character, Jacqueline, portrayed with a somber and restrained demeanor by British actor and singer Cynthia Erivo, longs for both solitude and safety. As a formerly affluent Liberian woman, educated in England, she is left destitute on a Greek tourist island after being forced to flee her country due to civil war. Jacqueline rejects charity and companionship, seeing human connection as a danger.

“I am not a refugee,” states Chen as he speaks through Zoom from his current residence in Hong Kong. Even though he cannot relate to being a refugee, there is a sense of displacement that he personally connects with and believes that he may never fully understand. Originally from Singapore, Chen moved to the UK to study film-making at the National Film and Television School and has since built a reputation for creating movies set and filmed in Asia. While his wife’s job has recently brought them to Hong Kong, he still considers London to be his home. Being an outsider, he has always searched for a sense of belonging and this theme can be seen in his work as he explores the themes of displacement and forming deep connections with strangers.

In 2013, Chen’s acclaimed film Ilo Ilo, which received the Camera d’Or award for best debut at Cannes, focused on a Filipino housekeeper who moves to Singapore and becomes part of a wealthy local family. His 2019 film, Wet Season, follows a Malaysian Chinese language teacher struggling to adapt to life in Singapore. Chen’s latest project, Drift, produced by a collaboration between Britain and Greece, is not a major departure from his past works. When he first read Alexander Maksik’s book, A Marker to Measure Drift, he was immediately drawn to the protagonist Jacqueline’s story. As the film was being developed during the pandemic, the character’s story continued to resonate with him.

“It was a deeply cathartic experience, as we were all confined to our homes and it seemed like the world was coming to an end. For me, Jacqueline and the pandemic became intertwined and the film served as a catalyst for healing. However, in light of current events such as the situations in Ukraine and Gaza, where there is immense displacement and suffering, the film has taken on an even more poignant meaning.”

He is concerned about how the film may be perceived as solely focusing on the refugee crisis. Instead, he hopes viewers will recognize the universal human element at its core. He expresses his concern that audiences may be hesitant to engage with thought-provoking films, assuming they are already well-informed about the refugee crisis from news outlets like The Guardian. However, upon watching the film, he believes they will realize its value and be glad they invested their time in it.

On March 29, cinemas in the UK and Ireland will be open.

The person in opposition is Milad Alami.

“There is a transitional place between embarking on a new life and remaining in the past,” discusses Milad Alami, a filmmaker originally from Iran who now resides in Denmark. He delves into the refugee experience with his poignant and impactful second film, Opponent. Alami speaks about wanting to portray this world from an internal perspective, showcasing its beauty and the hopeful anticipation for a new beginning, as well as the challenges of adapting to a new life and carrying the weight of one’s past.

The main character of Opponent, Iman (portrayed by Iranian-American actor Payman Maadi, known for his role in Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation), carries a heavy burden that ultimately leads him, his wife, and his family to flee Iran. Iman, a professional wrestler, has always hidden his attraction to other men due to it being illegal and punishable by death in Iran. When his relationship with another wrestler is exposed, Iman must escape the country immediately. While starting a new life in Sweden may offer him the freedom to be his true self, Iman struggles with balancing his identity as a gay man and his role as a committed husband and father. Director Alami explains that it was crucial to have a character who outwardly seemed to have full freedom but internally had to make choices between different aspects of his personality instead of embracing them all.

Although Alami was just six when he arrived in Sweden with his family at the end of the 1980s (they fled the country for political reasons: “My dad was politically involved and against the Iranian regime”), he drew on his memories of being an Iranian refugee when writing the screenplay.

Many parts of the movie reflect my personal experiences. I intentionally chose to have the film take place in the same location where I lived in the 1980s – the north of Sweden. This setting mirrors the snowy and isolated environment that is portrayed in the film. My own recollections of that time are positive. I recall enjoying my time at a refugee center, playing, and socializing with others in the snow. Everything was new and exciting. However, there was also a sense of unease and pressure, likely stemming from the uncertainty my parents felt about our future in this new place. Ultimately, their main concern was whether we could remain here permanently.

cannot reword.

,

On April 12, cinemas in the UK and Ireland will be showing…

Source: theguardian.com