L

Maulud Emhamed Sidi Bashir is currently residing in a tent outside of his home, where he is listening to a compact, silver portable radio. In the Sahrawi refugee camps, located near Tindouf in the south-western region of Algeria, it is common for individuals to assemble traditional tent structures like the one Bashir is in, adjacent to more modern structures. The electric guitar melodies emanating from the radio, to which the 75-year-old is listening, encompass a fusion of both conventional and contemporary styles. Bashir’s family members claim that many of the tunes originate from a musical group known as El Wali.

The nature of El Wali can be difficult to determine as there is limited information available on Google and only one album on YouTube, without any credit for the singers or musicians. The band’s origin in the Western Sahara remains a mystery to most people. However, El Wali has evolved into a national orchestra, with songs that have no credits and do not belong to any specific individual. It is a constantly changing entity that has members that come and go over the years.

Lud Mahmud, a member of the Polisario Front independence movement, attempts to clarify while driving through the Hamada desert. He gestures towards the camp dotted across the flat, rocky landscape, stating, “This is El Wali.” As they continue driving and arrive at the next camp, he repeats, “This is El Wali.” The idea is evident: all aspects of Polisario music are encompassed by El Wali. While some members may stay in the band for an extended period, there have been numerous individuals who have been part of the camp, with each one likely providing more than one contribution.

Located between Morocco and Mauritania, this desert was once a Spanish territory and one of the remaining European colonies in Africa until 1975, when Spain returned it to Morocco. The indigenous people of Western Sahara, known as Sahrawis, were made up of nomadic tribes with little sense of national identity before being displaced by Morocco. In the late 1970s, they sought shelter in the southwestern region of Algeria where they came together in opposition to their common oppressor and established their own nation, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR).

The Polisario Front, a left-leaning group, initiated a rebellion against Morocco, which has been ongoing up to the present time. The dispute has recently escalated, particularly after former US President Donald Trump acknowledged Morocco’s assertion of authority over the region in 2020. Despite being largely ignored by the global community, this is one of the lengthiest conflicts in Africa, representing an ongoing struggle against colonization (Western Sahara is defined as a non-self-governing territory by the UN, effectively a Moroccan colony).

Both Bashir and Mahmud were part of the large group of individuals who were forced to abandon their homes in Western Sahara and take refuge in camps located in Algeria. Here, the Polisario utilized music as a means to instill a collective sense of national identity. Ancient poems that revolved around the conflict with Morocco were transformed into melodic tunes, incorporating a mix of traditional and modern instruments. This captivating fusion was performed by a band that would eventually be known as El Wali.

“I have my origins in the midst of war,” recalls Ahdaidhum Abaid Lagtab, a previous member of the band El Wali, as the current band performed in the Laayoune refugee camp. “I arrived during the occupation and I remember the Sahrawis who lost their lives.” Lagtab was only 16 when, like Bashir, she escaped the Moroccan army’s attack in the late 1970s. “Our songs did not focus on political agendas, but rather on societal issues. We sang about liberty.”

In 1979, she became a member of El Wali, a band that was already established with approximately twelve members. The band took its name from El-Ouali Mustapha Sayed, a co-founder and well-known martyr of the Polisario Front. El-Ouali had a rock star appearance and the charm of Che Guevara, and he inspired the emerging nation until his death at the age of 28 during a raid in 1976. He remains revered as the ultimate hero of the Sahrawi people.

In a world where contracts and copyrights dictate much of the music industry, we often view bands as existing in specific time and place. However, for El Wali, this is not the case. According to band member Salma Mohamed Said, also known as Shueta, the band initially formed as a national project, with artists from different districts being chosen to join. Some played traditional instruments, while others played modern ones, creating a balance between the two styles. Shueta, a veteran singer and drummer who has been with the band since its inception, fondly recalls their travels and performances in the 1980s and early 1990s, which took them to various countries across the globe.

In 1994, El Wali traveled to Belgium to participate in a recording session coordinated by Oxfam. Managed by Hilt Teuwen, the production welcomed the band Shueta. Teuwen contacted the band after meeting them in the refugee camps and invited them to Belgium. The end result was a high-quality recording of their album Tiris, featuring 13 songs and three vocalists, as well as the use of electric guitar, bass, drums, keyboard, and tidinit, a traditional Sahrawi lute. The album is a blend of joyful and nostalgic melodies, recounting the history of the war against Morocco and the aspirations of a displaced people for independence. Although the band’s lineup has changed, El Wali still exists and they maintained communication for some time after the recording.

Without Christopher Kirkley, a guerrilla ethnomusicologist and producer from Oregon, the world, particularly the west, may have forgotten about Tiris. In 2009, Kirkley travelled through the Sahel and west Africa to gather musical recordings for his album project, Music from Saharan Cellphones.

Cannot reword

During that period, he stated, the internet was not widely accessible in the area. Instead, mobile phones and Bluetooth were commonly used for sharing and listening to music. The primary method of obtaining songs was by transferring them from one phone to another, essentially creating a network of music exchange. While conducting his research, Kirkley continually came across songs by El Wali on memory cards and sim cards, but he did not know the identities of the performers. Due to a lack of available information, the songs were often simply titled as “Polisario.”

Kirkley notes that Sahrawi music played a significant role in bringing the electric guitar to the region, and this instrument gained widespread popularity in West Africa during the 1990s. Many well-known styles of Tuareg guitar music, which are also known as desert blues or Tuareg rock and performed by acclaimed artists such as Mdou Moctar and Grammy-nominated Tinariwen, drew heavy inspiration from Sahrawi guitar music. Kirkley explains that the upbeat and reggae-influenced rhythms of this music have their roots in Sahrawi music, making it a defining sound of Western Sahara.

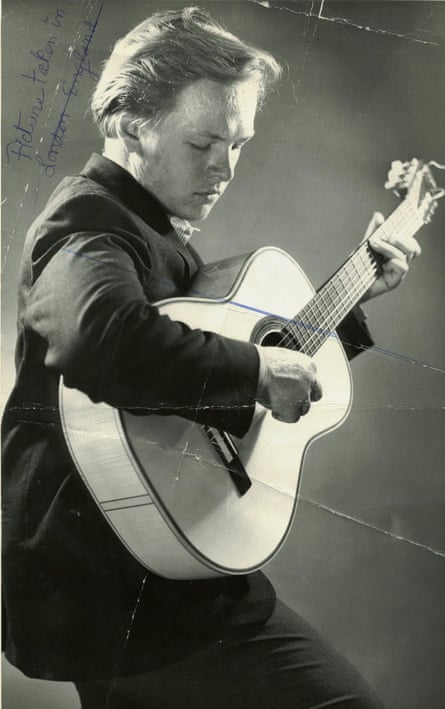

After the 2012 release of Music from Saharan Cellphones Volume Two, the author embarked on an eight-year quest to uncover the origins of the popular Sahrawi songs featured on the region’s mobile phones. He reached out to Hamdi Salama, a Sahrawi music producer he met through individuals working in NGOs in Western Sahara. Hamdi then connected him with Ali Mohammed, the guitarist on El Wali’s Tiris, who revealed details about the recording session in Belgium under Oxfam. The studio engineer, Pierre Jonckheer, who recorded the album, also happened to have a CD copy of Tiris.

Kirkley states that the CD in question cannot be found anywhere in the world and has disappeared from the internet and western media. It is intriguing that the music has managed to survive and resonate solely through phone networks, giving it a new lease on life.

In 2019, Kirkley and Salama relaunched the release of El Wali’s Tiris on Spotify and YouTube, the platforms where the initial story unfolded. They are currently in the process of releasing new music from the Sahrawi band. According to Kirkley, “The new album features a completely different group of individuals.” It can be challenging to introduce this new release to an audience and confirm that it also falls under the name of El Wali.

In the desert, the 50th anniversary of the Sahrawis’ fight against occupation is being commemorated with a grand national parade. The military plays a major role in the day’s events, showcasing outdated rockets while onlookers brave the scorching sun from atop their vehicles. As night falls, music takes center stage. Shueta, a familiar presence, performs from exile, singing about the homeland that many in the audience have never seen. Yet, the electrifying chords of the guitar hold the hope of a future Sahrawi state and the enduring melodies of El Wali.

Source: theguardian.com