Little Richard – Long Tall Sally

Rock’n’roll is nearly 70 years old: it can just sound arcane and distant to ears trained on 21st-century pop. An effective crash course in its revolutionary importance, how it changed Britain forever requires not one track, but two. First, play something that constituted pop music before Little Richard et al arrived: Dickie Valentine’s The Finger of Suspicion, Anne Shelton’s Lay Down Your Arms or Guy Mitchell’s frankly horrifying paean to fatherhood, Feet Up (Pat Him on the Po-Po). Then play Long Tall Sally, the feral opening seconds of which – in the context of what came before – sound like a bomb going off, or the world being turned on its head. Alexis Petridis

Dave – My 19th Birthday

In November 2017, Santan Dave had just turned 19 – already a relative veteran of UK rap, having spent two years making his name with pained, punchy lyricism about his young life and British society. He released his second EP, Game Over, and My 19th Birthday was the final track, clocking in at nearly nine minutes. Over melancholic piano keys, he opens by recalling how he spent his recent birthday in hospital with his brother and mum for reasons unknown, before launching into a single, spiralling verse of relentless wordplay and raw expression. It’s a crisp example of how, beneath the bravado, a rapper’s recording studio can and does provide a vital cathartic space: a chance to purge negative emotions for its writer and, in turn, feel empathy among listeners. Ciaran Thapar

Albert Roussel – The Spider’s Feast

Impressionistic classical music can do wonders for kids’ imaginations, especially if it depicts wildlife. But why stop at Sibelius’s serene tone poem The Swan of Tuonela or Saint-Saëns’ musical tour of the natural world, The Carnival of the Animals, when you can offer the spider, dung beetle and dancing fruit worms of Roussel’s 1912 ballet The Spider’s Feast? The music portrays a spider waiting to dine on goodies trapped in its web, only to discover that nature is full of surprises. A parable on greed and the cycle of life, it’s a work that is also ripe for interpretative dance – in costume! Phil Hebblethwaite

Terry Riley – In C

Everyone starts at the beginning, but after that it’s anyone’s guess how each performance of In C will turn out. Terry Riley’s minimalist breakthrough, which caught the public’s imagination in 1964, is a rolling bubble of chaos and sweet harmony. The players – any number, any instrument – work their way through 53 tiny cells of notation at their own pace, kept in time by a single metronomic pulse. If there’s a fine line between creative anarchy and classroom omnishambles, In C is a magic spell to get everyone in tune. Chal Ravens

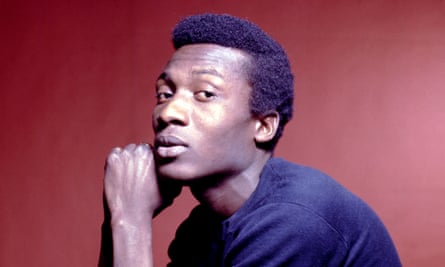

Jimmy Cliff – Many Rivers to Cross

Jimmy Cliff wrote this astonishing song in 1969 when he was 25 about his struggle to make it in Britain after early success at home in Jamaica. But its meaning extends way beyond that and becomes ever more relevant as millions try to escape poverty, civil war and human rights abuses across the globe. Many Rivers to Cross is one of the great songs about migration: a reminder to our schoolchildren – and more importantly, Keir Starmer and Labour – that you can’t turn your back on human rights and outsource your morality, no matter how many cheap votes you think it might buy you. Simon Hattenstone

Kero Kero Bonito – Only Acting

When you’re a kid, there are no rules to making art: ripping up a picture and sticking it back together the wrong way still creates a valid finished product. By the time you hit high school, art has a bunch of rules. Teachers tell you there’s a “right” and a “wrong” way to sing, paint, sculpt, make films. In reality, that’s bullshit, but it can take years to learn that. Only Acting, by Kero Kero Bonito, breaks every rule of pop music: it has a weird narrative, it changes styles at least three times, it’s uncomfortably noisy, but it’s still perfect pop. I think a lot of people could have skipped a wasted decade trying to follow arbitrary rules had they given it a few spins at a formative age. Shaad D’Souza

Joanna Newsom – Bridges and Balloons

I have known many a small child captivated by Joanna Newsom and it’s not hard to tell why: with her flowing dresses, majestic harp and a voice that manages to sound both youthful and wizened, like being gifted wisdom by a twisty sapling, she could easily have sprung from the pages of a storybook. And therein lies the lesson: in her unabashed romanticism she is her own creation, a testament to keeping imagination alive. As a lyricist, her curiosity extends to the natural world, to the cosmos, to the heart; beyond standard verse-chorus-verse form to stake out new territories. It’s all driven by a linguistic joy and sensitivity that is there for any kid to pluck for themselves like a ripe apple, before it’s ground down by rote assessments and spelling tests. In Bridges and Balloons alone, there are caravels, catenaries, dirigibles – acorns of discovery that might grow in any direction a budding mind chooses to cultivate. Laura Snapes

after newsletter promotion

John Coltrane – A Love Supreme

If you want to inspire children why not start with the best piece of music from the 20th century? A Love Supreme is John Coltrane’s definitive album, a masterpiece. The fact the whole suite starts with a four-note bass line before expanding into an ambitious but approachable suite of music is a crucial lesson on how less can be more. The whole 33 minutes might be a bit much for six-year-olds to get their heads around, but even just a bitesize chunk of its recurring motif, religious overtones and use of improvisation will be more than enough to get curious minds thinking. Lanre Bakare

Metallica – Master of Puppets

You may scoff at the idea of noisy metal making it on to the school syllabus. But hear me out. Metallica’s magnum opus is often hailed as the genre’s greatest text, epitomising the California thrashers’ collision of brute force, instrumental technicality and surprisingly accessible melodies. Plus, beyond that, it’s a cathartic thrill ride: a ferocious outpouring that could be life-changing for students stifled by the UK’s stiff-upper-lip state school system. Feelings like frustration and anger were treated as taboo during my education, and music like this offers a non-destructive outlet for those inherently human emotions. Matt Mills

Dolly Parton – Coat of Many Colours

To tell a story through music is to have great power, and few do it as well and with such longevity as Dolly Parton. Fundamentally, this is a song about poverty. It is about going to school in a coat made of rags given by a neighbour, with “holes in both my shoes”. It speaks to Parton’s own life growing up poor in a one-room cabin with 11 siblings and newspaper on the walls. And it might say to the many kids in Britain who find themselves in destitution today that they are seen, they are known, and that there are people who still care – even if this government does not. Jenny Stevens

Jonathan Richman – Corner Store

Art may be viewed by those in government as a luxury reserved for the well-off, but my children’s teachers creatively sneak it into most lessons as a way of looking at more traditional subjects from a different angle. I was tempted to choose Judy Collins’ upbeat version of Both Sides Now, perhaps the ultimate song about viewing things from a fresh perspective (and with its line about ice-cream castles, it has a built-in art project raring to go). But Corner Store tells a simple story about a very modern phenomena that many kids will see around them – small businesses being replaced by bigger chains, to the detriment of local character. The learning opportunities are endless, especially around the history of the neighbourhood. And if you think an end-of-year play about rampant gentrification is a bit on the serious side then remember it has a chorus that goes: “Bam a nib a nib a nib way oh / Bam a nib a nib a way oh web oh!” Tim Jonze

Source: theguardian.com