I

In early 2022, Wim Wenders was unexpectedly invited to Tokyo to view a collection of public toilets. The invitation was from the Tokyo Toilet art project, which had enlisted renowned architects and designers to construct 17 visually appealing public restrooms in different areas of the Shibuya district. Wenders recounts with a smile, “They reached out to me, knowing my interest in Japan and architecture, and asked if I would be willing to visit their stunning toilets. If I approved, they suggested I create a series of short documentaries about them.”

The invitation arrived at an opportune time for Wenders, who, as he puts it, was “feeling very homesick for Tokyo”, a city he had visited often since since making a film about the fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto in 1989. “It seemed,” he tells me, “like a dream come true.”

After taking a brief break from filming the last scenes of his documentary about Anselm Kiefer, a German artist, he traveled to the city. Seeing the beauty and tranquility of the smaller areas there, he was inspired to create a fictional feature film that captured the same atmosphere. He promised the people hosting him that he could make the film on a small budget and within 16 days of shooting. Surprisingly, they agreed without hesitation. Looking back now, he realizes it all happened quickly, but he sees this speed as a blessing that allowed him to freely express his creativity.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

The final outcome, however, is a demonstration of the art of slow cinema. Perfect Days is a movie where not much occurs, but the few events are strangely captivating. Written together with Japanese writer Takuma Takasaki, it consists of a series of subtle variations on one theme: the daily work routine of Hirayama, a lone but satisfied person whose task is to clean and upkeep the Shibuya toilets. “It may be a small film, indeed,” Wenders acknowledges. “But it was also my first film after the pandemic. I saw it as a fresh start for myself, so I wanted it to have significance.”

During a time when the film industry is flooded with grandiose and lengthy works like Oppenheimer and Killers of the Flower Moon, Wenders’s contemplative exploration of the uncomplicated life has resonated with both critics and audiences. Last May, Kōji Yakusho, who portrays Hirayama, received the best actor award at Cannes. Wenders stated, “His character is the heart of the film.”

Where did the inspiration for this stoic protagonist originate? “I created him in my mind and we selected him within two weeks. We were aware from the beginning that we needed someone who was observant and could convey their surroundings through their eyes. It takes a skilled actor to portray subtle actions, like opening a door or looking up at the sky, and make them meaningful. There was only one person I knew who could fulfill this role and that was Kōji.”

The movie is being considered for the top international feature film award at the Academy Awards, marking the first instance of a non-Japanese director being chosen by Japan. Takasaki praises Wim’s impressive grasp of Japanese culture and expresses delight in collaborating with him. Their partnership allowed for a fresh perspective, leading to a rediscovery of the country, its culture, and its principles.

I met Wenders at the expansive headquarters of his production company, Road Movies, located in the Mitte district of Berlin. We conversed across a long table in a back room, with a tall African carving standing guard by the door. One wall was adorned with Wenders’s large-format landscape photograph of the American west. At 78 years old, the director exudes a sense of calmness and his responses are thoughtful and thorough. He ruefully remarks, “Films are now seen as products.” He goes on to explain the appeal of Perfect Days, stating that he had no one watching over his shoulder and had the freedom to do as he pleased. While Takuma was a great help, there was no control and they were allowed to run free. Despite having limited funds, they had complete creative freedom.

His 23rd feature film, Perfect Days, has been praised by critics as a comeback for a director who has received more recognition for his documentaries in recent years. These include Pina (2011), a depiction of the influential and minimalist dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, and Pope Francis: A Man of His Word (2018), in which he was given unprecedented access to the current leader of the Catholic Church. However, these films did not prepare me for Anselm (last year), which I consider to be the most thought-provoking and enlightening exploration of obsessive artistic brilliance.

The filmmaker expresses satisfaction in successfully completing a difficult project despite the challenges of the pandemic. The film was shot over a three-year period with seven different shoots in various locations, and post-production lasted for a few months. The ample time spent on this movie allowed for a deeper understanding and portrayal of the subject’s extensive work.

I viewed Anselm and Perfect Days back to back and was amazed by their contrasting themes and goals. “Absolutely,” he chuckles. “They are practically polar opposites. To begin with, I have never encountered someone as dedicated as Anselm Kiefer. He is unyielding. On the other hand, Perfect Days centers on a man who lives a minimalistic and uncomplicated life. Thus, one focuses on abundance while the other highlights simplicity.”

Yakusho portrays Hirayama, the janitor, with incredible accuracy, presenting him as a man who seems out of place in modern society. He has left behind a more privileged life for unknown reasons and now resides in a modest apartment in a working-class neighborhood. Hirayama spends his free time reading literature from secondhand bookstores and listening to a small selection of cassette tapes, including the Kinks, Nina Simone, and the Velvet Underground, in his van during his commute. During his lunch break, he quietly observes the world around him from a park bench and occasionally takes photos of the nearby trees. In the evenings, he frequents the same cafe and bar.

His interactions with passing characters, including his feckless workmate, his adoring niece and a stranger who is terminally ill, are fleeting but meaningful. The arrival of his estranged sister in a chauffeur-driven car, her obvious wealth a signifier of his previous life, briefly unsettles his equilibrium, but throughout he remains a man apart, someone who has found a profound inner peace through the simplicity of his routine life. “I think of him as a kind of secular monk,” says Wenders.

Display image in full screen.

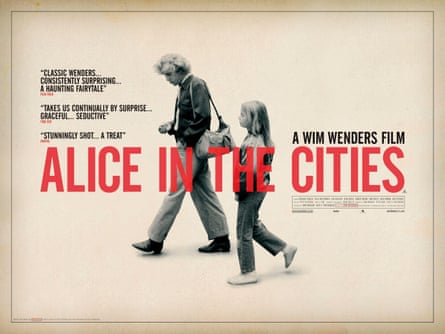

Hirayama stands in stark contrast to the restless characters that appear in the director’s earlier works. These characters, such as Philip Winter in 1974’s Alice in the Cities and Travis Henderson in 1984’s Paris, Texas, are constantly searching for something but never seem to find it. In contrast, Hirayama is content and not on a search for anything. The director agrees, stating that his previous films were about searchers while Hirayama is not. He takes a moment to reflect, stating that all of his films ultimately deal with the question of how to live. Despite not realizing it at the time, the director was also searching for answers. However, his film Perfect Days provides a clear answer. He believes that many viewers will watch it and long for a simpler way of life, with less focus on consumption. In many ways, Hirayama embodies this ideal way of living.

W

Wim Wenders became a prominent filmmaker in the early 1970s along with other notable German directors such as Werner Herzog and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who were part of the New German Cinema movement. Born in Düsseldorf in 1945, Wenders’ path to filmmaking was not straightforward. He was raised Catholic and briefly considered becoming a priest before studying medicine and philosophy. However, after dropping out of university to pursue painting in Paris, Wenders developed a passion for cinema, often watching multiple films in a day at his local Montparnasse cinema. He returned to Germany in 1967 and worked as a film critic for various publications while attending film school in Munich. Wenders notes that the same film school had previously rejected Fassbinder and lacked even basic equipment.

Radical inspiration arrived in the form of the slightly older Werner Herzog, a visiting lecturer whose message to the students was, as Wenders says, “intense and brutal” in its directness. “Nobody teaches cinema like Werner,” he says, laughing. “He told us to quit school immediately. He shouted: ‘You are idiots if you stay here. It is not getting you anywhere. You have to leave this school tomorrow and start to make films. You will never do that if you stay in this place.’”

I inquired if you followed his suggestion. “No, but it did alter my perspective on film-making. I owned a 16mm camera and began creating films outside of school. I also became the designated cameraman for all my classmates, thanks to my little Bolex camera. We proceeded to make a new movie every week from that point on. Our learning came from hands-on experience, mostly due to Werner’s insults.”

Having completed his early “road movie” trilogy – Alice in the Cities, The Wrong Move and Kings of the Road – Wenders became more well-known with 1977’s The American Friend, a stylishly noirish adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel Ripley’s Game. Between 1974 and 1982, Wenders was married and divorced three times, each time to actors, including Ronee Blakley, who starred in his 1985 docu-drama I Played It for You. (He has been with his current wife, Donata, a photographer and sometime collaborator, since 1993.) Despite his creative productivity, he describes the 70s as a dogged time for him personally. “I was in really bad shape back then and I took a long, but useful, detour into Freudian analysis. I did it five times a week. It was a full-time job.”

In the 1980s, Wim Wenders faced a difficult time while working on the film Hammett, a high-cost Hollywood thriller requested by Francis Ford Coppola. Coppola demanded a complete re-edit, causing Wenders to struggle. However, in 1984, Wenders regained his creative energy with Paris, Texas. This film also featured a solitary traveler, portrayed by Harry Dean Stanton. The film’s breathtaking landscapes, captured by Wenders’s longtime partner Robby Müller, along with its haunting music and evocative imagery, including billboards, train tracks, and desert highways, solidified Wenders’s reputation as a European filmmaker with a romantic American sensibility.

Display the image in full screen mode.

A few years later, there was a sudden change with the release of another film that gained him recognition: Wings of Desire. This European film takes place in his hometown of Berlin and follows angels who roam the city as unseen beings. It is widely regarded as one of the most captivating depictions of Berlin’s unique atmosphere before its reunification. One of the film’s cameo appearances is by Nick Cave, who performs two songs with his band, the Bad Seeds, at a local club. At the time, he was living in Berlin. “I recently rewatched it,” he recalls, “and was struck by its accuracy in portraying Berlin during that time: the locations the angels traverse, the improvised bars they visit, the overall post-punk vibe of the city, and of course, the looming presence of the wall. There was a political undertone and a sense of a thriving artistic community that attracted many creatives to the city.”

According to Wenders, it took him an unusually long period to come to terms with being a German artist. He only fully recognized this after creating “Wings of Desire,” which he considers to be his film about returning to his home country. Prior to this, he had been avoiding Germany and instead exploring other nations and their cultures. He believed he was much happier and more successful outside of his own country.

W

Enders and Anselm Kiefer were both born in the year when Germany surrendered at the end of World War II. It took Enders three years to create his piece on Anselm, and one may wonder if he felt a connection to his subject due to their similar backgrounds. When asked about this, Enders responds, “Yes and no,” after taking a moment to think. He explains, “We went through many of the same experiences during our youth. I grew up on the Rhine River, just like he did a few hundred miles north. We both had teachers who were part of the Nazi regime, and we lived in a country that was trying to rebuild itself and move forward. However, for a long time, the idea of a future was contingent on erasing the past.”

Display the image in full screen mode.

Wenders’s intricate and multi-layered documentary reveals that Kiefer’s art has centered on questioning the Germany they both were born into. This includes exploring the aftermath of World War II, the silence surrounding it, and the collective amnesia that followed. Wenders reflects, “As a young person, you are aware that something is wrong but cannot quite grasp it. As you grow older, it becomes clearer and causes great unease. Personally, I was so unsettled by it that as a teenager, my only desire was to escape. Anselm, on the other hand, had a different approach. He wanted to confront it head-on, to expose it and remind people to never forget. He chose to stay and face the truth, while I did not.”

He admits that it took him a while to accept his German identity and embrace his inner romanticism. This realization came during his time in America, where he initially attempted to assimilate and create a movie with American influences, but ultimately realized that his German roots were too ingrained in him.

Wenders’ extensive journey as a movie producer has, to some extent, mirrored his personal interests, particularly his enduring spirituality. The celestial beings that roam and float above his hometown in Wings of Desire and its underappreciated sequel, Faraway, So Close!, are representations of Christian symbolism: divine judges of righteousness and grace. Hirayama in Perfect Days leads a nearly saintly life, though his temperament is more aligned with Zen Buddhism rather than Christianity. The director has also described his documentary on Pope Francis as the culmination of all his previous films. Ironically, despite being raised Catholic, Wenders converted to Protestantism in the 1970s after a revelation during a service at “a very lively Presbyterian church” in Los Angeles. I inquire if he still considers himself a religious individual, as his later works suggest.

“I consider myself to be a highly spiritual individual,” he responds. “This means that I am deeply religious, but not particularly fond of organized religion. When I came back to Berlin, I was unable to find a church that had the same vibrancy and sense of community as some American churches do. The type of religion I am drawn to is similar to the early churches, where there was a sense of communal living and almost a communist society. The limited information we have about them has greatly influenced my life, with their emphasis on sharing and living simple lives. Unfortunately, much of that has been lost over time.”

In the film Perfect Days, director Wenders has crafted the character of Hirayama as a modern-day saint, living a simple but contented life free from the constraints of organized religion. The movie quietly celebrates the idea that a fully lived and mindful ordinary life can have a spiritual aspect. This idea is reminiscent of Wenders’ cinematic idol, Yasujirō Ozu, whose films also had the power to change one’s perspective on the world. Even in telling a commonplace family story, Ozu’s films are elevated by their portrayal of humanity and spirituality.

He expresses disappointment that many successful films today are “franchises” – movies based on other movies. However, he remains an eternal optimist. Recently, his optimism has been severely tested. He has been working on a science-fiction utopian film called “Peace By Peace” for the past five years, which includes a significant part about Palestine. Unfortunately, he cannot continue with the project as planned. Due to recent events, he must rewrite the film as the basis he wanted to use is now destroyed. He fears that Palestine may not even exist anymore and will become a wasteland.

In summary, I inquire if he sees his creative journey as a continuous thread driven by similar concerns. His response is that he is currently in a different mindset. In his youth, the experiences of his characters mirrored his own quest in a peculiar manner. Filmmaking was a journey in and of itself, a process of uncovering the underlying truth of the narrative being told. However, there is now less opportunity for that, which is why he focuses on making documentaries.

He takes another brief pause. “I discovered early on that creating films is a transformative experience. It changes you into someone else. Sometimes I wonder what my life would be like if I had pursued my childhood dream of becoming a painter. I believe I would be a very solitary, serious, and introverted person. However, film-making expanded my mind and my personality. I used to be a loner, but not anymore.”

-

The release date for Perfect Days is 23 February in the UK and Ireland.

Source: theguardian.com