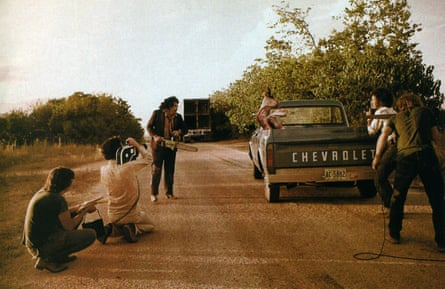

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre arrived much like its hulking antihero, Leatherface: without warning and with a sickening blow to the skulls of unsuspecting audiences. Despite its bare-bones production and lack of actual gore, the 1974 movie carved a new path for horror film-making, and key elements were the eerie sound design and abstract score: perfect matches for the film’s red-raw storytelling and stark imagery. But despite its enduring influence, the soundtrack has never had an official release until now.

Put out by Waxwork Records, it has been painstakingly stitched together – rather like Leatherface’s horrific mask – from the original recordings, and it is startling: a cloying series of drones, scrapes, clanks and groans that draw a jagged line to genres like industrial, noise, dark ambient and musique concrète. “We really wanted the mind of the viewer to do some of the work rather than it being ‘here’s the Leatherface theme,’” says Wayne Bell, now 73, who originally composed it with director Tobe Hooper. “We loved the idea that our score tested the edge between sound and music. That boundary was a wonderful place to hang out.”

As well as the score, Bell was part of the team who captured the film’s on-set sound, and created the incidental sounds that fuelled the film’s dread-filled atmosphere. “The low-budget films I worked on in the beginning were all up-from-the-bootstraps, shoestring kind of stuff where we had to improvise and be inventive,” he says from his Texas home. “I’m glad I came up that way.”

By the time he started working on Chain Saw aged 21, Bell already had form: he had worked on Hooper’s warped hippie flick Eggshells and a hit radio show, and sound and music were part of his upbringing. His father was an accomplished fiddle player; “There was piano in the house and I was expected to learn how to play it, which I sort of did,” Bell says drily. “It was a core aesthetic: music is valuable. Your life is less without it. It established music as an important part of your environment as opposed to just sound that comes out of the radio.” Bell’s father had lost his sight early in life, and during family TV time Bell became attuned to the relationship between sound and image. “If the music, dialogue and sound effects didn’t make clear what was happening, he’d want to know,” says Bell. “So I tuned in to what the soundtrack is telling you – and when it’s not telling you anything.”

Bell met Hooper in the summer of 1969, through a friend who was working on a film about folk act Peter, Paul and Mary. “Tobe was co-owner of a film production company,” says Bell. “I graduated from high school on a Friday and was in at this film studio the next Monday – the first thing I did was paint the walls.” Bell had been experimenting with recording and editing sound since middle school, and Hooper noted his abilities during Eggshells’ all-hands-on-deck production. This made Bell a natural choice for Hooper’s next feature, which initially laboured under the working title Head Cheese.

Having worked with Ted Nicolaou (later a horror director himself) to capture Chain Saw’s live sound, Bell joined Hooper in post-production, creating a library of sound effects: creaking doors, caved-in skulls and pig squeals, the latter provided by Bell’s father. “At a certain point Tobe said, ‘You know, we could do the score ourselves,’” recalls Bell. “There wasn’t the money to hire musicians or a composer, so it was kind of, ‘No solution? No problem!’”

Bell assembled a grab-bag of equipment: cymbals, a much-tormented upright bass and a lap-steel guitar, as well as wildlife calls, toy instruments and a saucepan courtesy of Hooper’s then-girlfriend, Paulette Gochnour (whose spare room also served as a makeshift studio). Despite a musical education encompassing everything from opera and Latin jazz to the 13th Floor Elevators, Bell says there were no specific guidelines for the soundtrack, not even the avant garde composers it is somewhat reminiscent of. “I was aware of John Cage, Stockhausen and 12-tone serialism but that wasn’t on my mind at all,” he says. “Playfulness and a willingness to try odd stuff were the only real relations between us and Stockhausen. We weren’t thinking of ourselves in that mode, just that abstraction would work for the film.”

True to its shoestring budget, the final film was completed on the fly with only Hooper able to attend the sound mixing in California. Hooper died in 2017 and the final assemblage was lost.

The newly released soundtrack is “rebuilt from the original parts”, says Bell. “There were hours and hours of recordings, so it was difficult. Plus there was a lot of self-imposed pressure – I really wanted this to be what Chain Saw fans want to hear.”

After Chain Saw, Bell’s career spanned sound, composition and voice work for film, TV and radio. He collaborated with Richard Linklater, produced a radio documentary on US politician Barbara Jordan and oversaw the session that became Stevie Ray Vaughan’s In the Beginning live album.

“I’ve got this wonderful body of work and the one thing that people remember is Chain Saw,” Bell muses. “The fact that it’s beloved still baffles me a little. It used to baffle me a lot.”

Source: theguardian.com