“I have been alone with a piano in the corner of a room since I was 15,” Bill Fay reveals. “I am not someone who seeks attention.”

This statement is not fully accurate. The mysterious 80-year-old has been involved in the music industry since 1967, but there is only one recorded live performance of Fay available online – a single song on Later… With Jools Holland. He has no desire to be in the public eye. “I make music solely for the love of it,” he states.

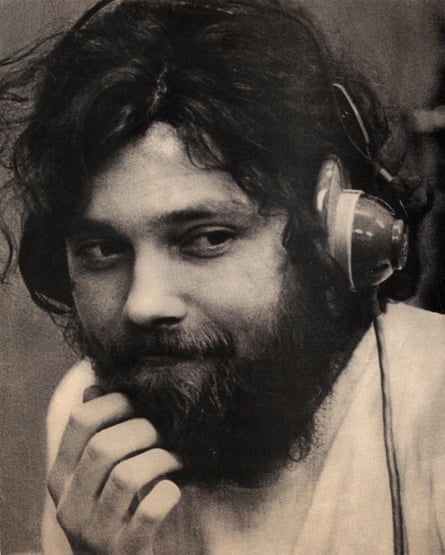

Fay has selected a Toby Carvery as his meeting spot, an improvement from the car park he previously chose for his short appearance on Radio 4’s Today show in 2012. As soon as he arrives, he stands out among the lunchtime patrons. He is sporting round glasses with yellow-tinted lenses, a suit, and a trilby hat, with unruly grey curls that match his beard. He is accompanied by an assistant and appears fragile. He shares that his Parkinson’s disease has significantly progressed. Interviews were always infrequent for him, and he mentions that this one will likely be his final one.

Our discussion was sparked by the debut of Tomorrow Tomorrow and Tomorrow, a musical collection created by the Bill Fay Group (featuring Bill Stratton, Rauf Galip, and Gary Smith) in the late 1970s but never officially published. It remained undiscovered for many years until it was released by Current 93’s David Tibet in 2005. Now, it is receiving a vinyl release for the very first time. Combining elements of art rock, folk, and subtle jazz influences, the album seamlessly blends melancholic ballads with innovative elements, all while showcasing Fay’s consistently gentle vocals.

Fay, a native of north London, spent his entire life in the area and was raised not too far from our current location. He cultivated his musical abilities by playing the piano at home and continued to develop his skills while attending college in Wales, where he started writing and producing his own songs. His demo recordings caught the attention of Terry Noon, a previous member of Van Morrison’s band Them, who assisted him in securing a record contract.

In 1970, Fay released his first album under his own name, featuring a rich blend of rural folk and pop music that would later be likened to Nick Drake’s style. His second album, 1971’s Time of the Last Persecution, is a remarkable display of personal reflection and struggle with religious beliefs, as he searches for hope amidst the looming threat of the end of the world.

The album gained a following, including Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy, who said, “It spoke to me on a personal level. There is a straightforwardness and grace to it. You can tell that this was not created for fame or trendiness; it is simply someone humbly sharing their voice to add some beauty and perhaps find peace in the world.” Unfortunately, the album did not do well commercially, leading to Fay losing his record contract and not releasing any new music for many years.

Fay refers to these years as his “deleted” years. He explains that he did not leave the music industry, but rather, it left him. However, he does not hold any bitterness. He states that it was not a challenge because he still had the music. He adds, “You discover the songs. And then you discover another one. That is satisfactory for me.”

Fay expresses his songwriting process as being beyond his influence. He states, “I am not a musician by trade, but rather a seeker.” He explains that the piano played a significant role in his upbringing and gradually taught him how to play. He relies on his intuition and the melodies that naturally flow to inspire his lyrics, which he does not write down. This process is almost like a mystery to him.

During his time away from the music industry, Fay held various jobs such as a groundskeeper, fruit picker, factory worker, and fishmonger. Despite this, he continued to make music using a simple home recording setup, never imagining it would reach an audience. One day in 1998, while gardening, he listened to some of his unfinished songs on his Walkman. He was surprised at how good they sounded and thought to himself that maybe one day someone would hear them. That very same day, he received a phone call informing him that his first two albums were going to be reissued.

Fay’s impact had quietly expanded without his knowledge. Musicians like Jim O’Rourke became enthusiastic admirers. It took a while, but Tweedy eventually convinced Fay to perform with Wilco in 2007, covering his song “Be Not So Fearful”. Tweedy fondly recalls it as one of the most memorable nights of his life. Around the same time, Marc Almond was also covering Fay’s music and Nick Cave invited him to join Grinderman on tour, hailing him as “one of the greats”. Of course, Fay declined the invitation.

A talented artist and music producer by the name of Joshua Henry stumbled upon Fay’s music while going through his father’s collection of records. As his dad was battling cancer, the two bonded over Fay’s music, and Henry made a promise to find and collaborate with Fay. However, contacting Fay proved to be a difficult task as he is notoriously elusive and surrounded by eccentric individuals. After numerous attempts, the two finally connected and hit it off right away. Henry was amazed by the quality of Fay’s songs and described the experience of recording with him as being in the presence of a musical genius like John Lennon.

In 2012, the album Life Is People received critical acclaim, followed by Who is the Sender? in 2015 and Countless Branches in 2020. A new group of fans emerged, with praise and renditions of the songs from artists such as the War on Drugs, Kevin Morby, Julia Jacklin, Cate Le Bon, and Mary Lattimore.

Fay often downplays his impact on other songwriters. He humbly acknowledges, “I am aware of it and grateful for the sentiment.” However, he finds it difficult to fully comprehend and internalize. While writing a song, he is focused on his own emotions and not on how others may feel. Once a song is complete and he is satisfied with it, he moves on to the next one without dwelling on its impact. He does not spend time reflecting on his influence.

He opens a package containing nicotine lozenges and discusses his early years of development. “Certain images have a lasting impact,” he explains. “Hiroshima; African Americans being lynched. The young girl whose back was burning in Vietnam. As a young person in that era, these things really affected me.”

Fay approached life with a weary perspective, but viewed it through the lens of Christianity. He delved into the highs and lows of existence, as well as the beauty and suffering that come with living on Earth. He describes himself as a seeker, and during the creation of his first album, he focused on the wonders of the world while sitting in his garden. He recalls being struck by the intensity of a passing bee and reflecting on its contrast to the vastness of the universe. With his subsequent album, Fay delved even deeper into this darkness, creating what he describes as a weighty and apocalyptic sound that reflects the current state of the world.

Is he still facing difficulties in finding hope amidst the troubling events happening in the world? “That is a profound question,” he responds, followed by a long pause. “There is always a balance of good and bad, but having faith is crucial.” Is he referring to religious faith? “Yes,” he confirms. “I struggled with this concept when I was younger because it seemed limiting, but I eventually came to believe in Jesus and studied prophecies. I felt that there would be some kind of intervention.” Does he still hold onto this belief? “It cannot continue like this indefinitely… there has to be some sort of resolution.”

Despite clearly still being distressed by the same subject matter that shaped his songs more than 50 years ago, Fay is no longer making music about it, or about anything at all. “I haven’t played a piano for three years due to Parkinson’s,” he says. “But I’ve got lots of songs in progress recorded. What’s out there is really just a fraction – there are piles.”

Does he take pride in his music? “I can’t say for sure,” he replies, struggling to utter the word. “I’m simply grateful.” He extends both hands and gently clasps mine in a warm handshake before getting up to return to his preferred spot: the corner of a room.

Source: theguardian.com