Tom Priestley passed away at the age of 91. From a young age, he knew he wanted to pursue a career in the arts. However, he realized that his father, the well-known playwright and novelist JB Priestley, had already made a significant impact in the field. Tom was the sixth child and the only son in the family.

He ultimately pursued and excelled in the field of film editing. He received a Bafta award for his work on Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), a dark comedy directed by Karel Reisz that explores themes of conformity and rebellion, and features David Warner and Vanessa Redgrave. He was also recognized with an Oscar nomination for his contribution to John Boorman’s thriller Deliverance (1972), starring Burt Reynolds and Jon Voight. The film is based on James Dickey’s novel about four friends who encounter terror from locals during a canoe trip in Appalachia.

Boorman remembered screening a preliminary version of the movie to Warner Bros executives: “The reaction was something that I became accustomed to, which was that individuals simply left without speaking. They were quite affected by it.”

Priestley expertly created an atmosphere of tension and unease in the film, highlighted by three unforgettable moments that have become iconic in the world of suspense cinema: the intense “duelling banjos” scene, the terrifying ambush where one of the men is sexually assaulted at knifepoint, and the shocking ending that leaves both the characters and viewers reeling with electrifying surprise even after the main events seem to have ended.

He was attuned to instances of impulsiveness as well. “Much of the scenes involving the river were essentially improvised because they were actively participating,” he noted. “For instance, if the canoe unexpectedly turned or someone’s hat fell off, we integrated those moments into the final version.”

Priestley was the editor for Boorman’s earlier movie, Leo the Last (1970), which was a satire about social class in west London and starred Marcello Mastroianni. He collaborated with the director once more on the unfortunate horror sequel Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) after the initial editor left the project.

Some of his other works include Marat/Sade (1967) directed by Peter Brook, The Great Gatsby (1974) featuring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, The Return of the Pink Panther (1975), Tess (1979) which was adapted by Roman Polanski from Thomas Hardy’s novel, and Times Square (1980), a drama about teenage punks.

Michael Radford, the director, collaborated with Priestley on the editing of the films Another Time, Another Place (1983), which tells a story of love during wartime in Scotland; 1984, a film based on George Orwell’s novel of the same name, released in that year and featuring Richard Burton’s last performance; and White Mischief (1987), which was inspired by a true murder case involving the British elite in colonial Kenya.

Priestley valued the preservation of emotion in his philosophy of editing, favoring it over traditional methods.

He was born in London and grew up there, living in a house that used to belong to Coleridge. He also spent time in a home on the Isle of Wight. His mother, Mary (nee Holland), who went by Jane, was previously married to the humorist DB Wyndham Lewis. She was passionate about studying birds and eventually wrote books about them with her third husband, David A Bannerman. Tom’s godfather was the author of Peter Pan, JM Barrie. As a baby, Tom attended rehearsals of one of his father’s plays called Dangerous Corner.

He described his early childhood as “a traditional upper middle-class nursery life … There was a nanny who looked after me and my younger sister. We were a separate group. If there were no guests, then we were allowed down for Sunday lunch.”

When he was eight years old, he was enrolled in Hawtreys, a boarding school in Kent. He was given permission to listen to his father’s radio broadcasts during the war, called Postscripts. During his upbringing, he was used to his father being away often and not visiting him at school. When they were together, there was a certain emotional distance. He admitted, “Honestly, my father preferred women. I believe they were more significant to him than I was.”

After attending Bryanston school in Dorset, he served in the Royal Engineers for his national service. He went on to study classics and English at Cambridge, where he organized a play-reading club that was attended by EM Forster. Upon completing his degree, he spent a year teaching English in Athens.

After going back to London, he secured a position as an assistant film librarian at Ealing Studios and transitioned into sound work. His initial acknowledgment was for serving as an assistant sound editor on Dunkirk (1958). He also held the role of sound editor for Polanski’s intense thriller Repulsion (1965), although he had since shifted into film editing.

He worked as an assistant editor for Bryan Forbes’s film Whistle Down the Wind (1961), which tells the story of three children who confuse an escaped prisoner (Alan Bates) for Jesus. He also worked on Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963), which stars Richard Harris as a rough rugby player. He served as the supervising editor for two surreal and innovative dramas that captured the state of the nation: Anderson’s O Lucky Man! (1973), in which Malcolm McDowell plays a coffee salesman on a bizarre and hostile journey through Britain, and Derek Jarman’s punk masterpiece Jubilee (1978), featuring a time-traveling Queen Elizabeth I.

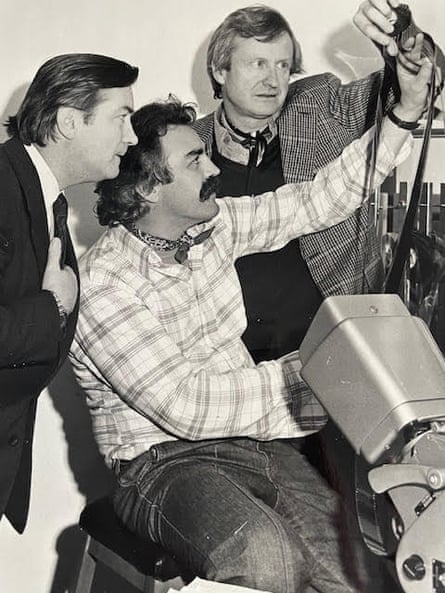

Display the image in full screen mode.

In the beginning of the 1990s, Priestley decided to stop editing because he felt that he had reached his full potential. He believed that his work was only using a small part of himself and that life was reduced to the images he saw through his editing machine. He had a strong feeling that he needed to engage more with the world and connect with others.

He accomplished this by instructing at the National Film and Television School and by celebrating his father’s legacy and accomplishments. He had previously created a film about his father, titled Time and the Priestleys, as a way to honor his 90th birthday. However, it turned into an obituary when his father passed away right before its release in 1984 at the age of 89. He continued to oversee his father’s estate until his own passing, assisting with the planning of events for his father’s centenary in 1994 and serving as president of the JB Priestley Society.

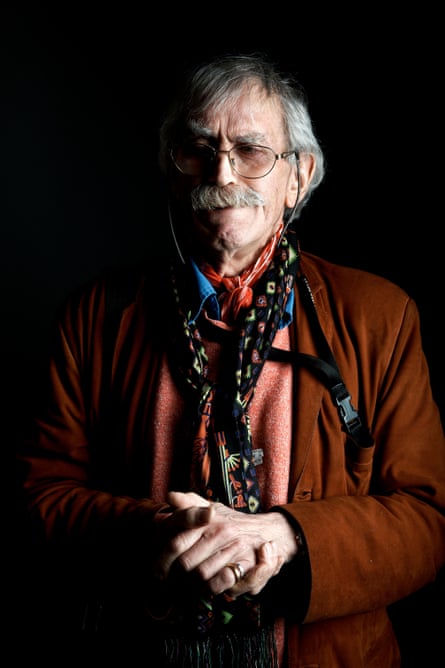

Tom was known for his impeccable sense of fashion, often being referred to as a dandy. When he received an Oscar nomination in 1973, the Evening Standard dedicated two pages to showcasing his wardrobe. The article praised his confidence in his personal style and noted that he was not self-conscious, but rather liberated. It highlighted his unique fashion choices, such as wearing a Moroccan kaftan instead of a traditional dressing gown and a hooded Arab cape while dining out locally. The paper also made note of his winter mustache and “Byronic” hair.

His appearance was a minor source of friction with his father. “It would be going too far to say he was jealous of me,” he told the Oldie in 2016, “but he was deeply offended by my jeans.” He was also “disappointed” to discover Tom was gay, and found it “difficult to adjust to”. Tom’s response: “Well, so did I.”

He is survived by sixteen nieces and nephews.

Source: theguardian.com