L

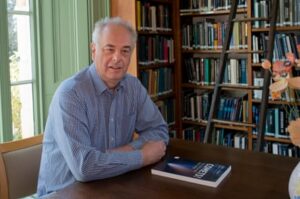

Pablo Patiño pondered the concept of phantoms before conceiving a film that could be experienced with closed eyes. Patiño’s initial two movies, Coast of Death (2013) and Red Moon Tide (2020), showcased the coastal scenery of his hometown of Galicia in an ethereal and grandiose manner. The region’s myths, apparitions, and forewarnings of demise intertwine as residents recount tales of maritime accidents, fishermen gone missing, and whispers of a mythical sea creature.

“I have been delving into the realm of contemplative film,” explains Patiño, age 40, regarding his previous projects. “I desired to delve deeper into the concept of an introspective and meditative encounter.” This led him to ponder “the concept of the unseen in film. Suddenly, the idea of creating a movie to be experienced with closed eyes emerged.”

The film Samsara, which takes its title from Buddhist beliefs about the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, begins in Luang Prabang, a city in the north of Laos. The main character, a teenager, often visits an elderly woman named Mon who is not in good health. He reads her excerpts from the Bardo Thodol, also known as the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which is traditionally read aloud to guide the deceased towards their next life. He also spends time with a friend who is studying at a Buddhist monastery, and together they hike through forests and waterfalls while discussing their future goals (the monk wants to study computers, while the teenager dreams of becoming a rapper).

As Mon says goodbye and passes away, she expresses her desire to be reborn as an animal. This is followed by a 15-minute pause where viewers are encouraged to imagine and accompany her through the afterlife with their eyes closed. When the interlude ends, we are transported to a family living on the coast of Zanzibar, with the beautiful blue ocean in sight. A young girl is overjoyed to witness the birth of a baby goat.

The film Samsara had its UK debut at the London film festival in October, with a showing at the BFI Imax. The grand setting of the Imax was a perfect fit for the film’s immersive and detailed sensory experience. The landscapes were stunning on the big screen, and the sounds were intentionally varied in intensity. Director Patiño reflects on how the idea of a closed-eye film had been on hold for a year or two until he stumbled upon the Bardo Thodol, which sparked an interest in exploring different cultural perspectives on death and the afterlife. Combining a closed-eye sequence with a story about the afterlife seemed like a perfect match.

He then had to make a decision about the locations. “I needed to find a place with a strong Buddhist culture,” he explains, considering the importance of the Bardo Thodol. He was drawn to Laos because its history is not well-known in Spain. He also mentions that Thailand was not an option due to the meditative and spiritual nature of the work of Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Patiño envisioned the second part of the film to be set in a completely different world, and the idea came to him after being invited to Tanzania for a film workshop. He spent 12 days filming in Luang Prabang and eight days in Zanzibar. He arrived with a team of three from Spain, but the rest of the production, including the camera crew and actors, were locals. He explains that this was due to the film’s low budget and his desire to minimize their impact on the locations. “We were very aware of our privilege as Europeans,” he says, and mentions how the process was collaborative, with input from the local crew and actors on the script. “We were fortunate that they trusted us and our intentions,” he adds. He believes that it is important to have open dialogue and curiosity between cultures, rather than solely focusing on one’s own cultural identity, as it can lead to nationalism.

The movie combines real-life elements with fictional elements, featuring scripted scenes as well as unscripted moments where individuals express themselves freely. One example is a lengthy conversation among women working at a seaweed farm in Zanzibar, where they discuss their frustrations with the contamination of their crop by water from a nearby hotel. It is mentioned that the men do not participate in this labor because it is deemed ungrateful. Death and various mourning practices are also recurring themes in the film, reflecting the idea of major changes on the horizon for the characters. In Laos, a young monk is approaching his 18th birthday and must decide whether to continue living in the monastery or not, according to Patiño. These stories serve to encourage viewers to contemplate their own choices and consider alternative ways of living. As a director, Patiño hopes to challenge our perception of how life can be lived.

Even with eyes closed, the screen in Samsara’s afterlife interlude is constantly in motion, filled with vibrant and changing lights and sounds that intertwine. Patiño took inspiration from American artist James Turrell’s light and movement piece titled “Breathing Light” in Los Angeles, describing the experience as inhaling and exhaling light. He also mentions Brion Gysin, a British-Canadian artist known for his avant-garde work, specifically his 1959 creation called the dreamachine. This was the first artwork to be experienced with closed eyes and consisted of a rotating cylinder with slots around a lightbulb. As the cylinder spun, the light from the bulb would flicker over the viewer’s closed eyelids.

In the meantime, the audio is divided into two parts: the initial portion features Xabier Erkizia, the sound designer for the film, interpreting descriptions of the afterlife found in the Bardo Thodol. The second part includes recordings taken by Erkizia during his career from various locations around the world, such as a conversation between a girl and her grandfather in Switzerland, and a woman cooking in Timor. These recordings symbolize the places where Mon’s soul is enticed to be reincarnated. According to Patiño, this section is “rich with hidden details”.

Patiño’s most recent film, Samsara, is heavily focused on storytelling. He often combines elements of video art and artistic cinema in his work, which typically showcases slow-moving landscapes and sometimes completely eschews traditional narrative. In a review of his film Red Moon Tide, The Guardian noted that its hypnotic pace and mystical contemplation may not be suitable for viewers seeking a straightforward viewing experience. When asked about his penchant for creating meditative films in today’s fast-paced world, Patiño explains that his fascination lies in “discovering my own perspective on physical reality”, similar to a painter carefully capturing the intricate details of a landscape.

However, he acknowledges that requesting people to close their eyes for 15 minutes, when they could see 2,000 shots in that amount of time, is a significant request and almost a form of resistance. However, he also notes that there is always someone in the audience who approaches him afterwards and says, “I will never forget this experience.” When asked why, he believes it is because they are suddenly asked to close their eyes in a film and discover something incredible.

Source: theguardian.com