T

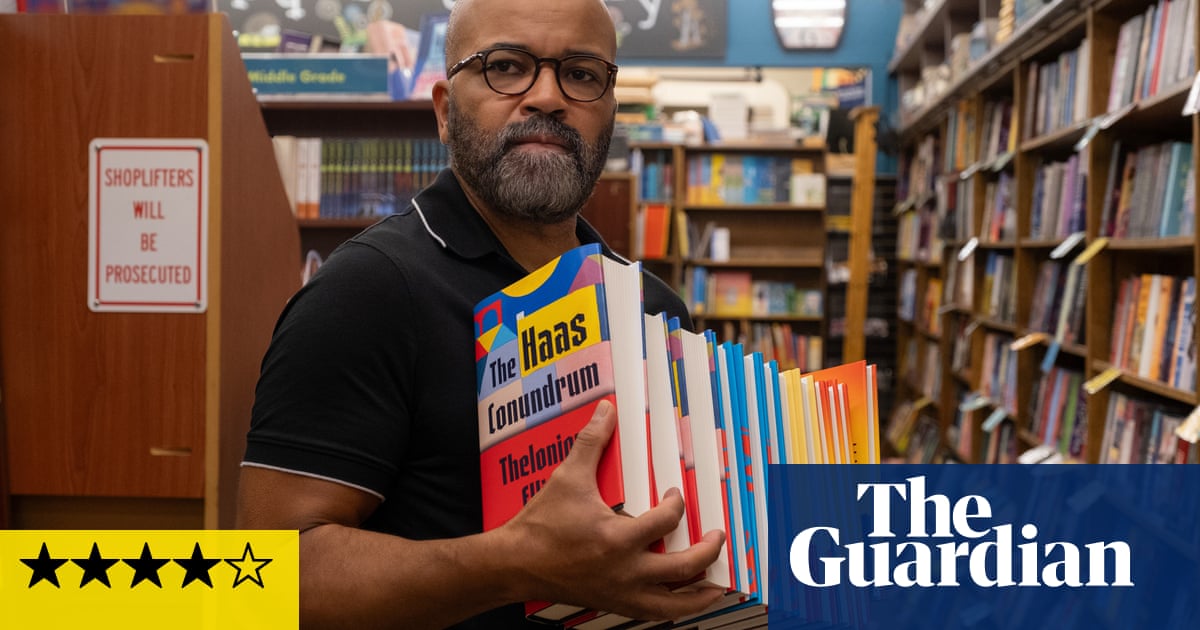

Helonious “Monk” Ellison is a middle-aged professor of humanities in Los Angeles who is disliked by both his students and colleagues. He has written several complex and unsuccessful novels based on classical mythology. Struggling with his career and financial worries, including caring for his elderly mother who has dementia, Monk becomes enraged when a new bestselling novel by black author Sintara Golden is praised for perpetuating stereotypes typically favored by white cultural gatekeepers. In response, Monk writes a satirical hood-violence novel titled “My Pafology”, under the pseudonym Stagg R Leigh, and sends it to his agent, assuming its crudeness will convey its ironic intent. However, things take an unexpected turn, similar to the storyline of Max Bialystock and Leo Bloom’s Broadway career.

Cord Jefferson, a filmmaker and television writer, has created a highly entertaining literary comedy called American Fiction. In this film, Jefferson makes his feature directing debut by adapting Percival Everett’s metafictional masterpiece, Erasure, which was originally published in 2001. The talented cast includes Jeffrey Wright as the protagonist Monk, who is sensitive, morose, and idealistic in a self-destructive manner. Tracee Ross Ellis plays Lisa, Monk’s shrewd sister who is a physician, while Sterling K Brown portrays Cliff, Monk’s brother who recently revealed his sexuality. Leslie Uggams gives a moving performance as Monk’s mother, Agnes, and Issa Rae plays Monk’s rival, Sintara Golden. Despite Jefferson adding some extra sweetness to the original story and making some changes, such as altering Lisa’s profession, the film is still enjoyable to watch.

Despite facing a difficult challenge, American Fiction has managed to succeed. This is exemplified by the works of Michael Winterbottom and Frank Cottrell-Boyce, who adapted Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy in A Cock and Bull Story in 2006, and Harold Pinter, who adapted John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman in 1981. These adaptations boldly attempted to portray the meta-levels of narrative in a realistic manner. However, Everett’s original novel stands out because it includes the entire text of “My Pafology” in the middle section. This allows readers to fully immerse themselves in the absurdity and exaggeration of the text, while also appreciating its thrilling energy. One may even wonder if the author himself considered attempting a bestseller like this, but ultimately settled for presenting it in quotation marks.

When adapting this story for the screen, Jefferson may have considered featuring the main character, Monk, as a sophisticated film professor with a screenplay titled “My Pafology” instead of a novel. This screenplay could have been inspired by a film like New Jack City, which is mentioned in the text. In the end, Jefferson explores these ideas and creates a humorous and captivating fantasy that examines the intersection of class, race, and literary preferences. It also serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of succumbing to societal pressures and hypocrisy. Additionally, it cleverly delves into the theme of literary jealousy as Monk’s imitation of a rival’s work reminded me of Kingsley Amis’ own experience with envy in his memoirs.

after newsletter promotion

In one instance, Jefferson creates a confrontation between Monk and Sintara where Sintara defends her novel. Some may view this as a loss of satirical boldness, especially since the author’s name is clearly a parody in the book. However, Wright and Rae deliver the scene with conviction, highlighting the snobbery in Monk’s reaction to Sintara’s success and potentially gendered undertones. Additionally, there is a comedic element when Monk has to publicly portray the slouching, tough Stagg R Leigh – but this may not be any more farcical than real-life situations such as the case of author Laura Albert, who was exposed in 2006 for creating a fake persona named JT LeRoy, who supposedly wrote authentically about her traumatic experiences, and even had her sister-in-law dress up as the reclusive literary genius. (It should be noted that the concept of erasure existed before this case.)

Although American fiction may be broadly generalized, its treatment of race and racism is indirect and surprising, and it cleverly pokes fun at the literary confinement within the publishing industry.

Source: theguardian.com