I

In a pirated recording from the 1990s, a group of Pakistani men wearing traditional shalwar kameezes are captivated as they listen to the powerful vocals of Zarsanga, a celebrated Pashtun folk musician from Pakistan.

For over 50 years, the uneducated girl from the village who transformed into the adored “nightingale of Peshawar” has sung traditional songs about yearning lovers turning to dust, Pashtun tribes’ respect for their ancestral lands, Pashtun women’s tribal jewelry, and leaving behind the darkness. With a veil covering her expressionless face, Zarsanga is reminiscent of a saintly figure. Her voice often elicits a fervor in some members of the audience who break into a variation of the Attan, a graceful circular dance believed to have been used by Pashtun warriors to intimidate Alexander the Great’s soldiers.

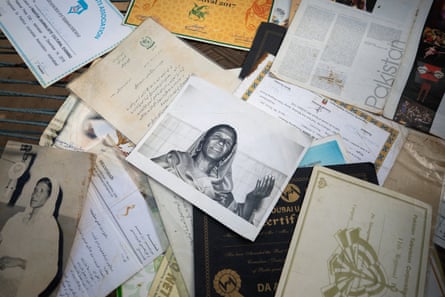

“I have encountered individuals who cry and others who bestow me with currency,” expresses a graceful and reserved 77-year-old, whom I come across on the periphery of Kohat, a city approximately an hour away from Peshawar. “I am grateful to God for my vocal abilities.”

Zarsanga’s voice was once widely recognized in Pakistan, but with the decline of cassettes and DVDs and the rise of new music genres, her music was seen as a remnant of the past. However, in 2018, she regained popularity with her performance on Coke Studio, a Pakistani music TV show sponsored by Coca-Cola. Her modern rendition of her classic song “Rasha Mama” received over 10 million views on YouTube. In 2021, she was featured on Malala Yousafzai’s Desert Island Discs and in 2022, she was chosen as one of the recipients of the prestigious Aga Khan award for music, sharing a $500,000 prize with 15 other awardees.

However, for over ten years, this well-known vocalist has been forced to live a nomadic and unpredictable existence due to being displaced by a flood in 2010. “I have been singing since I was a child, but I still haven’t been given any land by Pakistan,” she expresses with bitterness. “I am not sure why.” While the authorities in the area deny this, it remains true that one of South Asia’s most talented folk musicians is now residing in a mud house with a tent serving as a roof.

In approximately 1946, Zarsanga was born in the district of Lakki Marwat in north-west Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which is now part of Pakistan. During her time as a shepherd, she would serenade her father’s sheep and horses with traditional Pashto folk songs, often singing those of the late Kishwar Sultan and Gulnar Begum.

When Zarsanga’s father found out about the skill his daughter had developed in the lush fields and forests of Lakki Marwat, he initially discouraged her from singing. Although folk music is highly respected in Pashtun culture, the musicians themselves are often looked down upon. “However, my father listened to me and said, ‘If music is your passion, then you have my support,'” she recalls.

He brought Zarsanga, who was 20 years old at the time, to perform at a nearby wedding. During the event, she happened to meet a musician from the area who introduced her to Gulnar Begum, a well-known singer whose voice had been featured in numerous Pashto films. Despite a mishap with the cassette reel, Zarsanga successfully completed the recording and was then invited to perform on radio shows throughout the country.

Display the image in full screen mode.

She has made significant contributions to the folk culture of Pashtuns, the largest minority group in Pakistan who primarily reside in the north-west region. Due to past stereotypes that portrayed them as a militaristic race, Pashtuns have been unfairly associated with terrorism, violence, and political instability. Recent events such as the 2012 shooting of Yousafzai, the establishment of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement to protect the rights of Pashtuns, and the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan have only reinforced these negative associations, particularly in Pakistan’s north-west region where many Pashtuns reside.

Scottish author and historian William Dalrymple argues that modern history presents a narrow perspective. He points out that the Pashtun lands have produced remarkable miniature paintings, sophisticated philosophies, and beautiful examples of Islamic art such as Gandhara art, Timurid paintings, and ornate tile work in Herat’s towers and Kabul’s bazaars. These cultural treasures, however, have been forgotten and overlooked. Before the partition of India in 1947, the Pashtuns were known as peaceful people, as evidenced by Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a Pashtun leader who led one of the largest non-violent armies in history.

According to Rashid Ahmad Khan, a musician who obtained the first PhD in Pashtun folk music at the University of Peshawar in 2022, there were numerous singers similar to Zarsanga around a century ago. However, the utilization of this traditional style has disappeared in modern Pashtun music, except in the isolated north-west region where traditional folk music continues to thrive.

Zarsanga, along with her late husband, Mullah Jan, relied on a rich oral tradition of lyrics and melodies from tappa or landay poems – the oldest form of Pashto folk literature – passed down through generations. As the daughter of a shepherd who was unable to read or write, Zarsanga committed the poems to memory. She recalls, “We were uneducated, I couldn’t comprehend [the rehearsals]. I could only sing once I had fully memorized the lyrics.” The origins of these ancient lyrics are also unclear. According to Khan, they are a part of the Pashtun heritage, and belong to everyone.

Zarsanga has passed down her musical talents to future generations and is currently highly valued in Pakistan. In addition to receiving the Aga Khan award, she has also been honored with the President’s Pride of Performance prize and has been featured in the anthem of the Peshawar Zalmi cricket team. However, she and her family still reside in rented mud houses.

Maximize image viewing by switching to fullscreen mode.

In 2010, severe flooding caused over 12 million Pakistanis, including Zarsanga and her family of six sons, three daughters, their partners, and children, to be displaced. They had to take refuge in tents along the roadside after their homes in Azakhel (located in the Nowshera district in the north-west) were demolished. Later in 2017, Zarsanga was compelled to flee her town due to a violent altercation between her sons and their neighbors over a financial disagreement.

Due to unprecedented inflation rates and the aftermath of severe floods in 2023, Pakistan is facing immense challenges. In the midst of this turmoil, a seventy-year-old woman has become the sole financial support for her entire family. Despite submitting several applications and recording videos requesting financial aid from the government, Zarsanga has not received any assistance. Rashid Ahmad Khan, president of the Pashto literary and cultural organization Hunari Tolana, claims that Zarsanga and her family have received a sum of three to four million Pakistani rupees (equivalent to £8,500 to £11,200) from the government, in addition to the Aga Khan prize fund.

Despite her uncertain living conditions, Zarsanga remains popular and her fame extends to Afghanistan, where 40% of the population are Pashtuns. While the Taliban has banned music due to their interpretation of Islam, Afghan journalist Fatima Faizi, who now lives in the US, continues to support Zarsanga. Faizi recalls listening to Zarsanga’s music and dancing as a child, and praises her beautiful and powerful voice. Zarsanga herself is not very open about her personal life, but she speaks passionately about the Pashtun diaspora, noting the strong bonds and love between Pashtuns living in England, London, America, Germany, and other countries. She expresses her willingness to always sing for them whenever they desire.

In 2018, Zarsanga’s performance on Coke Studio introduced her to a new audience from around the world. The performance started with her traditional song “Rasha Mama” accompanied by the Pakistani folk band Khumariyaan playing the rubab and guitar, but later transitioned into electric guitar riffs and the soft vocals of pop singer Panra. The producers of the session, Zohaib Kazi and Ali Hamza, described it as Zarsanga’s way of passing the torch to the younger artists.

The duo aimed to bring attention to regional languages and music that had been overlooked during the upheaval following India’s partition in 1947, when Urdu became the dominant language in the country. According to Hamza, the post-partition urban culture focused more on economic opportunities and pleasing the white population. Kazi adds that their travels across Pakistan revealed a lack of representation for significant aspects of Pakistani culture, which is where Zarsanga’s role came into play.

In the past 50 years, the majority of well-known Pashtun folk singers have been women, such as Zarsanga, Sultan, Begum, and the late Qamar Gula. They are highly respected in a traditionally patriarchal Pashtun society where women typically do not hold public roles. According to Kazi, Zarsanga stands out as an exception, representing strength and rebellion as a female Pashtun singer. Her enduring success is a testament to her tenacity.

Unfortunately, due to the patriarchal society and ongoing discrimination against folk musicians in Pakistan, none of Zarsanga’s daughters have pursued music. She shares that no other women in her family sang before her, and it is possible that there will not be any future female musicians in her family.

Source: theguardian.com