Born in 1970, Alison Clarkson, AKA Betty Boo, is a singer-songwriter, rapper and producer. She grew up in west London with her Scottish mother, Malaysian father and brother, and her first group was rap trio the She Rockers. In 1990 she launched her solo career as Betty Boo. With her platinum-selling debut, Boomania, she achieved three Top 10 singles, a Brit award for best British breakthrough act, and international success, before stepping out of the limelight for three decades. During her hiatus, she co-wrote Hear’Say’s Pure and Simple (then the fastest-selling debut single of all time in the UK) and worked with Sophie Ellis-Bextor, Girls Aloud and Blur’s Alex James. She now lives with her film producer husband, Paul Toogood. Her new album, Rip Up the Rulebook, is out now.

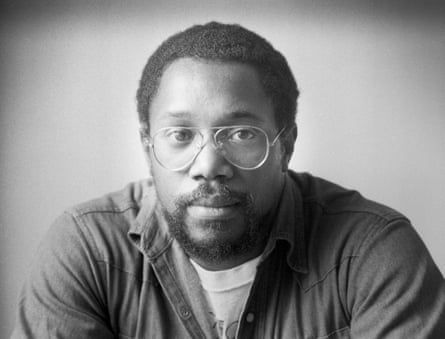

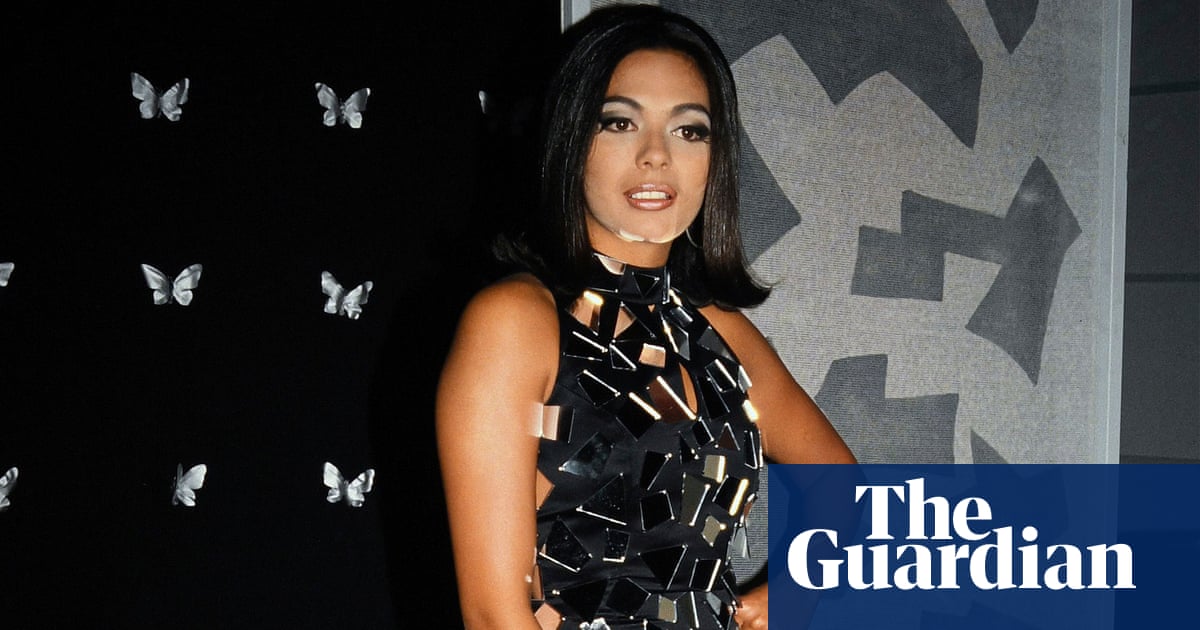

It was an exciting and surreal moment when this photograph was taken. I had just won a Brit award and there was so much attention on me it felt as if I was the bride at a wedding.

I had barely slept – it was a freezing winter, and the heating wasn’t working at my mum’s house where I was staying, so the cold had kept me awake. Thankfully the makeup artist covered up my bags. It helped that I had a sun tan from a trip to Los Angeles, and that I was buzzing on the adrenaline and excitement of it all.

My speech was quite random. I thanked Seymour Stein, who signed me to his label in the US, the UK record label Rhythm King, plus all of the pluggers. I ended with: “God bless Des O’Connor!” Earlier on in the ceremony there had been a tribute to his career, and people in the audience had laughed at it for being cheesy. Des had always been kind to me, so I wanted to give him props.

I was, and still am, painfully shy. Hiding behind a larger-than-life character is a way to navigate certain events without going red, and that’s what I’m doing here. The dress was by Arabella Pollen and inspired by Barbarella, which I loved because the 60s spacey kitsch look was key to what I was doing with Betty Boo. Yasmin Le Bon was there that night and said I looked amazing. My heart skipped a beat! I felt as if I was on top of the world.

I might have been shy, but creatively I was fearless. I was up against artists like the Charlatans, the Happy Mondays and the La’s in my category. What I was doing – combining rap with pop – seemed quite fresh at the time. Especially as rap had not been taken that seriously; it was seen as a bit of a fad.

Growing up as a female in the 80s and going to a comprehensive school, there weren’t many opportunities. There was no room for wild ideas about being a musician. I remember going to the careers adviser when I was a teenager and telling them I wanted to be a vet. Even that was rejected. They said I was more likely to be a secretary. Which was fine – that’s what my mum did – but it just wasn’t enough for me.

after newsletter promotion

It’s mad to think that a year before the photo was taken I was alone in my bedroom writing songs. As I wasn’t one of these stage-school, tap-dancing kids, I didn’t have a 10-year plan, but things were somehow taking off. I suddenly had bigger budgets and was treated like a superstar. I went from being on an indie label and getting picked up in battered old cars, to staying in the best hotels, getting free clothes and having an entourage. When I went on This Morning I took about 10 people with me. Judy Finnigan was not happy. She said: “Get them out of here!”

One of those 10 was my personal assistant, Meg Mathews, who ended up marrying Noel Gallagher. She would get me water and chopped fruit from Marks & Spencer – I was such a goody-goody compared with the rest of the artists in the 90s. Very boring, not at all rock’n’roll. In retrospect, I was very naive. I remember going to clubs and thinking: “Everyone’s so friendly! I don’t know why they keep saying they love me!” The next time I’d see them, they wouldn’t remember who I was. It was only years later I realised they were on loads of drugs.

At the height of my fame, I had an American management team who wanted to try to change me. They’d say: “We think you could do more dancing.” They’d suggest other ways I could dress. I was a proper bedroom musician and someone else taking control was a real turn-off. I’d rather stick pins in my eyes than go into some kind of pop laboratory. Sometimes their suggestions got to me; they made me feel I wasn’t enough. I remained pretty resistant, and was probably unmanageable in lots of ways. Not that I was a brat or prima donna; fame never went to my head.

I was at the top of my game when I had a series of bereavements that changed the course of my life. Dad had died in the late 80s, so when my mum fell ill with cancer, I wanted to make sure she felt safe, to stay with her and hold her hand. After we lost her, I had to look after my nanny, and moved her to Chiswick, in west London, where I was living. I became her carer and the captain of the family. This was at the end of the 90s. It was so far from being a pop star. It was as if a light had gone out, and I just didn’t feel like Betty Boo. The performing, the craziness of the industry – none of that mattered much to me any more. It’s taken me a very long time to come to terms with that grief. Loss took a while to hit, and never goes away, it just gets a bit easier. It wasn’t until I got married that I felt as if I belonged to a family again.

In the years that I wasn’t making my own music, I wrote for other artists, but I wasn’t that passionate about it. It’s a different kind of writing, more clinical; getting inside someone’s head and figuring out what they might think or say. It wasn’t for me.

Turning 50 was a transformative moment. My mum died when she was 49 and my dad at 47, so I thought: “Hang on a minute – I’ve just outlived both my parents, why am I not embracing life?” It’s a privilege to get older, and I want to make the most of every second, not worry about what I should sound like, or if my age matters. I found my co-writer and producer Andy Wright, who helped me open up and not hold back. Quite quickly, I returned to that 20-year-old version of Betty Boo. Now I don’t know what else I would do if I wasn’t writing my songs. Maybe work at a kiosk in Waitrose? I’ve always thought that would be nice.

Being embraced by a new audience has really helped with my confidence and reframed my career. I didn’t realise that Doin’ the Do is seen as a coming-out record to some people, or that it represented a kind of “brown‑girl power” for other mixed‑raced girls. That means a lot to me because, growing up, I got bullied for not looking like the other kids at school. I felt alien, but eventually used that difference to my advantage. “I’m so glad I’m not like everyone else,” I realised. “I am just me.”

It made me want to do my own thing; rip up the rulebook, which is still how I feel now.

Source: theguardian.com