In the video for the Manic Street Preachers’ latest single, Hiding in Plain Sight, we see bassist Nicky Wire getting ready to do his job. He sits in front of a lightbulb mirror, applies glittery eyeshadow, black eyeliner, then stands to add a feather boa, a sailor cap, a jacket covered in badges and home-sewn patches. The other two members of the Manics, guitarist James Dean Bradfield and drummer Sean Moore, along with backing singer Lana McDonagh, guitarist Wayne Murray and keyboardist Nick Nasmyth (who play in the Manics live shows) are playing their instruments. Also, because it’s the Manics, everyone’s reading books: Camus’ The Plague, Cynan Jones’s The Dig, Angharad Price’s The Life of Rebecca Jones. “The mirror is a trap that saves/Or a debt that makes you pay,” sings Wire, surrounded by Polaroids of the band when they were young: skinny, obstreperous, beautiful. “I wanna be in love /With the man I used to be/In a decade I felt free”.

It’s curiously defiant, the video. “Yeah, it’s got a bit of resistance to it,” says Wire. “It’s a warped nostalgia. It’s not pretending I can go back.”

Being reminded of your pretty, clever youth isn’t always easy.

“No, and in a band, you’re constantly bombarded with images of that. I know, it’s the male gaze but, when you look at yourself, you go, ‘Fucking hell.’ The cruelty of time … And when you realise how quickly it’s gone …

“On 1 February, it’s 30 years since Richey disappeared – that’s longer than he was alive. It does still emotionally floor me. Those images bring back brilliant memories. But you’re constantly challenged with how to repurpose your former self into now, for yourself. You know, I’m 56.”

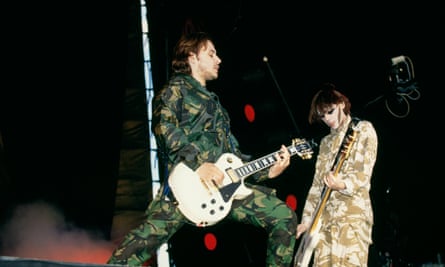

Ah, the Manics. Cleverer and more self-aware than almost every other band, with a unique, constantly present history. Since they started in 1986, they’ve never stopped. Four, now three working-class Welsh lads, friends since childhood – Nicky Wire, Richey Edwards, James Dean Bradfield, Sean Moore – they formed an upstart band with shiny songs and glittering ambition, and their 1990s rolled out like a film. Launching themselves as white-trousered, be-sloganned punk outsiders, their trajectory was smashed when, in 1995, Edwards’s precarious mental health deteriorated and he disappeared (he was legally declared dead in 2008). The three remaining members pulled off an exhilarating return with Everything Must Go and its anthemic single A Design For Life, and ended the 90s properly huge, shifting 5m albums and playing Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium on New Year’s Eve 1999.

After that, the Manics rollercoaster continued: self-sabotaging their success with the over-long and under-produced Know Your Enemyin 2001, coming back into favour with Send Away the Tigers in 2007, then following that with the bleak Journal for Plague Lovers, which used old Edwards lyrics. The push-me-pull-you of big tunes and challenging thinking. Over the last two decades their albums have all charted in the top five. They’ve never split up, never taken a break. In between Manics albums, Bradfield and Wire put out solo ones. What was it that Beckett wrote? You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on.

Their new album, Critical Thinking, is, oddly, not entirely like a Manics album. It’s bumpier, more intimate, with an occasional late-1980s indie feel. The big riffs and the hate lyrics are there, but also wistfulness, chiming Johnny Marr guitars, beauty and edginess. There’s OneManMilitia (“I can’t breathe when I hate this much”), but there’s also Being Baptised, about Bradfield meeting Allen Toussaint, which is just lovely.

Anyway. Wire may be 56, but he is still recognisably a rock star. Tall, tufty-haired and long-limbed, in large sunglasses, he looms by his car at Newport station, ready to give me and PR Gillian a lift to the Manics’ studio. We sit in the back at his request: “Too much stuff in the front.” His car isn’t messy – on the contrary, he’s obsessively tidy (when the Manics won Brit wards, for best British group and best British album – Everything Must Go – in 1997, he wore a homemade T-shirt that said “I Love Hoovering”) – but there’s a big bag in the passenger footwell, and, on the front seat, a large concertina file stuffed with papers. “My Malcolm Tucker folder,” he says, and smiles his shit-eating grin. He takes this file everywhere. It contains lyrics, memorabilia, “pressed flowers, hotel stationery” and band information.

Wire prides himself on being on top of Manics data: how many times a single gets radio play in Norway; who’s reviewed an album and what they’ve said. He can recall details of features I wrote about the band more than 30 years ago. “I’ve always been a mixture of incredible pettiness,” he says, “and incredible macro-level insight.”

I talk to him first, and then Bradfield (Moore doesn’t do interviews any more), in the Manics’ studio, which is a small cottage that faces out of a hill. Downstairs are the music rooms, including a sound desk from the famous Rockfield studios; upstairs is a lounge, with sofas, TV, running machine. All is workable, but not fancy. It was here that the band made Critical Thinking. Their 15th album, so you’d think they’d find it easy by now. But they didn’t, not entirely. Some songs came together without effort (People Ruin Paintings and Being Baptised), but for others, they had to retreat into their separate lives to stop disagreements and get things done. “The stubbornness of 50-odd-year-old men,” says Wire. “Entrenchment. The three of us are guilty of it – musically, politically, socially, everything. We’re just so familiar with each other’s quirks.”

Anyway, Wire wrote three songs entirely by himself, tune and lyrics, as did Bradfield, before bringing them in to the others. (Separately, they both praise each other’s abilities to me, saying that the other writes in a way that they can’t access.) And then, unusually, Wire sang the ones he wrote: Hiding in Plain Sight, Critical Thinking and Deleted Scenes. (Bradfield, blessed with a huge soaring voice, is the Manics’ singer; Hiding in Plain Sight is the first single that has Wire as vocalist.)

For other bands, this might not seem significant, but the Manics started with very definite rules and roles. When they became a band, after being close their whole lives (Wire and Edwards grew up one street away from each other in Blackwood, south-east Wales; cousins Bradfield and Moore shared a bedroom in Bradfield’s parents’ house), they wrote down what they wouldn’t do. No love songs, no drugs, no trip-out sounds, no encores. No pints, only Babycham. Bradfield, who I interview after Wire, says they even had their own food: “White trash and speed thrills, we called it: rice, mushrooms, peas, tuna, and a bit of chilli.” These strictures extended to how the band worked. Guitarist Bradfield and drummer Moore were the musical wing, so they wrote the tunes and Bradfield sang; bassist Wire and rhythm guitarist Edwards were the political wing, so they did lyrics and interviews.

Over the years, though, the band roles have blurred, partly because they all got better at what they do, partly because Edwards disappeared. Then, Wire took over the lyrics; Bradfield had to step into the gap of interviews and pics.

“There are so many myths in rock’n’roll and we were steeped in them,” says Bradfield. “I remember Richey going missing, and then two weeks later, just thinking, ‘Oh, is this it? Are we that story now?’ These things happen in rock’n’roll. I remember thinking, ‘Wow, it’s us. Fuck. It’s us.’ And then you reproach yourself and you go, ‘No, it’s his parents, it’s not us. It’s his sister, it’s not us.’ It was just. ‘I can’t believe this. I can’t actually fucking believe it.’”

They got through, he thinks, because of their work ethic. “Find the chord, dig in. The simplest answer. We went through a lot, but also it was like, ‘You signed up for a tour, son.’”

Wire says that he thinks about Edwards all the time. He imagines what he’d be doing now, “a cultural commentator”, perhaps. “He wrote so much, it would have just been endless articles and essays. A lyric like PCP [about censoring yourself for fear of falling foul of political correctness, which Edwards wrote in 1994] is such a portent of what’s happened.”

Along such Edwards lines is Critical Thinking’s title track, which, reassuringly for Manics fans, is a rant about what Wire hates about modern life. Funny and scathing, it mocks both trite Insta-captions (Live your best life / Be kind/ Be your authentic self) along with freeports and “smart fucking motorways”. “I love writing lyrics,” he says. “I can’t tell you how much of an art I think lyric writing is.”

after newsletter promotion

The band have always put their ideas and their politics in their songs, so they don’t have to explain what they believe, even when asked. But Wire can’t resist. He likes political discussion – “the left is really good at telling people off,” he says, “Which just makes everyone think: fuck off”. He says he knew that Trump would win the US election: “It was so obvious to me. Politics is much more about mood and gesture than policy at the moment, and we live in an age of spectacle and eventisation. When we made [2010 album] Postcards from a Young Man I went on about tech bros [on the track Don’t Be Evil]. People were bored shitless with me, but you’ve got Ballard talking about inner migration and how personal computers will change everything in 1981. And when they own their own platform, it’s just, how can you fight against that, other than ignore it? I don’t know.”

This, to be honest, is pretty mild from Wire. The band were made in the 1990s, when discussing politics or saying outrageous stuff was actively encouraged by the music press. The Manics were very good at this – memorably, Edwards said, “we will always hate Slowdive more than we hate Hitler” – and back then, says Wire, there was a celebratory aspect to it. “Music journalists could be absolute take-you-down motherfuckers, but they did elevate as well. They made bands sound even better than they were. But now, you’ve got to do everything yourself, and you can end up looking like complete tools.”

Which brings us to Dear Stephen, a new song about Morrissey, where Wire pleads for the singer to “come back to us”. Despite Morrissey’s rotten political views, he finds himself returning to both him and Larkin, “but not TS Eliot”, too antisemitic, which he knows is hypocritical. He shows me a postcard, from Morrissey and [late Smiths bass player] Andy Rourke, which he’s kept from his school days. He also has one from Lawrence from Felt. All in his file. He does go through and edit stuff, he says, and he keeps and has kept everything about the band in a lock-up. A Museum of Me? I joke, and he says, “Why not”. He’s also writing a memoir.

“My greatest strength,” he says, “has always been finding myself infinitely fascinating and dependable. But that’s waned a bit lately. We used to be defined by the opposition, but now I am my own opposition. It’s the first time I thought, ‘Should I be doing this any more?’”

Playing live is part of Wire’s worry. He doesn’t have impostor syndrome – “if the plumber comes round and asks me something, then I’ve got impostor syndrome. I haven’t got it when I’m fucking prancing around on stage” – but wonders if what the Manics do is enough in “an era of 200 dancers”. Still, they recently finished an international double-headliner tour with fellow working-class Britpop outsiders Suede, which he loved: “Not a cross word!” And there are aspects of touring that he enjoys. A nice hotel, a business lounge. In hotels, he nicks the stationery and also the shampoo. He notes that this was easier when the rooms had small individual bottles, but now, in an era of large shampoo bottles stapled to the wall, he simply brings his own mini-containers and fills them up. He mimes this. He is very funny.

Wire is a mix of wit and politics, combined with a whirring, neurotic, precise mind. Bradfield brings a different energy, a more random front-footed fizz, born of natural shyness mixed with physicality. He says he, too, loved playing alongside Suede, that he learned a lot from Brett Anderson’s “feral, wild” showmanship (he describes Anderson as like Roger Moore’s The Saint in everyday life, but a maniac on stage); but also how the members of Suede could go home – they live in different countries – and come back together. “It’s the chemistry,” he says. “You can’t mess with it.”

The Manics, all of whom live within half an hour of each other, definitely have a chemistry – they’ve always said that they love one another – but that love comes with frustration. Wire says that he tries to hug Bradfield just to piss him off: “He goes fucking mental”; Bradfield fall asleep anywhere but that gets on Wire’s nerves. And mystery man Moore, who seems even more mysterious these days with his long beard and eyebrow piercing? Bradfield, who’s known Moore for the whole of his life, says if he looks at Moore on stage, he refuses to look back. “He just won’t. I’ll get right in front of him and he turns his head away. And Wire wants nothing to do with doing the Rick Parfitt and Francis Rossi [of Status Quo] back-to-back thing with me, you know what I mean?”

Despite this, their loyalty to each other is unshaking and it extends everywhere in their working life: they have the same management that they did when they started, the same PR, they’re on the same label. Perhaps they would be more appreciated if they took a break, but when they did, both Wire and Bradfield brought out solo albums. Bradfield is thinking of maybe taking a year off, though I don’t believe him. “Would I get into whittling?” he says. “No. My dad was a chippy and a roofer and my mum was a bookkeeper and I inherited none of it.”

HeB gets rid of his energy by walking his dogs (two boxers: when I describe my dog, a jack russell mix, he says, “Oh a one-hour dog, mine are three-hour ones”). But also he, like Wire, can tie himself up with angst. “I used to be obsessed with watching European subtitled movies, and I got stuck in a really bad Swedish, Danish, German, Austrian, French movie mode, looking for inspiration on a beach, gazing into the fucking distance, you know? A lot of sepia filmic thinking,” he says.

Now, he tries to let ideas for lyrics wash through him. Be less precious, though he always wants to keep standards high (“Nicky’s so good, I’ve got to keep up”). He’s been learning Welsh and French (his wife is half-French) and wonders if that has helped. In Welsh, he says, you don’t say you’re depressed, you say, depression is on me. Really, he tries because of the band.

“Being in a band, it really makes you question everything about yourself,” he says. “You think it would be ego-affirming, but you start seeing the bad things that people say, and that smashes your ego. Then, when it comes down the other side, you realise you’re part of something which is really organic, and you’re much better with each other, it’s healthier. You just go, ‘Fucking hell. This is a self-sustaining little kind of organism,’ which is brilliant. I don’t have to care about whether people like me any more, I’ve got to care about if people like the band. The band feels like something you can go into battle with against the world. That’s what it’s about.”

-

Critical Thinking is released on Columbia Records on 31 January. They tour the UK in April and May 2025.

Source: theguardian.com