Candi Staton is part-way through a sprawling history of the days when she worked in a nursing home by day and sang in a bar by night, chasing her dreams of stardom while supporting her kids. She’s describing her one-time home – a $65-a-month apartment in “the worst part of Cleveland, Ohio” – when she pauses. “Oh my God,” she says, catching her breath for a second. “I’m telling you a lot!”

But there’s a lot to get through. There’s the sheer breadth of her work, for starters. Often dubbed “the queen of southern soul”, she started out in gospel before making forays into Americana, R&B, house, and just about everything in between, her career threatening to judder to a standstill several times over many decades, before speeding up once again. Staton’s voice is rich and warm, but there’s a bluesy, plaintive quality that underpins it; the singer Beverley Knight once summed up her hit You Got the Love as sounding like Staton was “looking at God and telling him: ‘Drag me through this, mate.’”

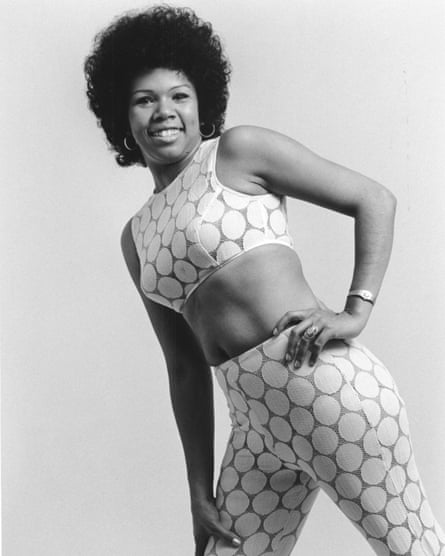

Then there’s her complicated personal life: Staton has five children, five ex-husbands, and has overcome horrendous domestic abuse. But, really, she packs a lot in because she is an excellent raconteur, an 84-year-old who seems to have forgotten to age (see also: her denim Gucci loafers and big sparkly elephant ring), and who possesses a quiet sense of steeliness and a ridiculously quick wit. Best known to many for the 90s remix of You Got the Love and her disco classic Young Hearts Run Free, she says the latter’s message of doomed romance and years “filled with tears” continues to bring new listeners her way. “The young people now, they listen to the lyrics, and that’s what they’re going through,” she says. “That’s why [the song’s writer/producer] David Crawford said it was gonna last for ever – because every generation goes through the same thing.” She quotes its lyrics: “You’ll get the babies, but you won’t have your man,” adding, “You’ll really get the babies now because they won’t let you have an abortion. In America? Forget it!”

Staton has travelled from her home in Atlanta to London for the UK’s Americana music awards, where she will be awarded a lifetime achievement gong. She will attend the premiere of a new documentary, I’ll Take You There, about the Alabama music scene, in which she features – and we meet in a dimly lit nightclub where the afterparty is due to take place later that night. It’s a busy few days, but Staton says she’s excited to be in town. Besides, it’s great timing: she’s also got a new album to promote, Back to My Roots, showcasing the kind of blues, gospel and country music she grew up on, alongside some original numbers.

In recent years, the likes of Lil Nas X and Beyoncé have ushered in the era of mainstream black representation in country, but Staton – who was born into a still-segregated Alabama in 1940 – was there long before, covering Dolly Parton’s Jolene and Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man. Before that, she was a gospel star. Even as a little girl, she would keep the whole house awake, she says, crooning with her older sister Maggie, who features on the new album. “My mother would come in and say, ‘Y’all trying to sing all night?’” she laughs. “Maggie and I have been harmonising together for ever.”

The Staton sisters grew up in the small country town of Hanceville with little money and few distractions, and singing became a beloved hobby. The pair were discovered by a preacher, Bishop Jewell, and dispatched to Jewell’s school in Nashville. There, along with Jewell’s own granddaughter, Naomi, the sisters were fashioned into the Jewell Gospel Trio. It was the beginning of a starry tweenage era for Staton, who – from the age of 11 – was “travelling all over the country, in limousines, on big stages, with big crowds … I was famous in the gospel industry.”

Audiences lapped up the pigtailed trio’s performances supporting Sam Cooke and Mahalia Jackson, with crowds dancing and jumping around frantically, sending chairs flying, and even rushing the stage. But, behind the scenes, things were less fun. As well as the rigours of travelling through the south as a group of black singers – which involved regular police harassment – the sisters were being exploited by Jewell. Candi and Maggie received no wages – not even a bit of change to buy an ice-cream cone, says Staton. She also recounts a dreadful episode involving an untreated tooth cavity she suffered in her teens, with nerve pain so bad that a fellow performer would hold her cheek on car rides between venues. Jewell’s solution, says Staton, was to put lye into the cavity, with cotton wool stuffed on top; Staton ran to the bathroom before the caustic substance could slip down her throat and potentially fry her vocal cords. Eventually, the police were called due to allegations of child maltreatment; Candi and Maggie lied and said they were happy with the Jewells. “I didn’t know how to deal with it as a child,” says Staton.

After that episode, the sisters didn’t stay with the group for much longer and, at the age of 17, Staton wound up back in Hanceville. Oil lamps still lit the streets and the bright neon lights of her travels – to New York and California, Cuba and the Bahamas – became a distant memory. Her mother had put the brakes on a mooted move to Los Angeles with Sam Cooke and another singer, Lou Rawls, a decision Staton now understands (“She said: ‘You’re not leaving at 18 with strange men,’”) but one that left her hurt and adrift at the time.

“I was back home with my mom,” she says. “It was a culture shock. I was so bored.” Boredom gave way to her first relationship, dancing the jitterbug with her boyfriend, a church minister named Joe Williams, on a Friday night and driving to get hamburgers and french fries on the weekend in his Chevy. A baby was conceived and born – the first of four with Williams, who would become her husband at her mother’s insistence. After seven years in an abusive marriage to Williams, Staton eventually got out, clawing her way back into the music industry, her children dispersed across different relatives’ homes without any support from their father. “I’m supermom,” says Staton. “I had to be mom and dad. I gathered strength from the weakness that people thought I was supposed to have.”

A more stable marriage – albeit adulterous, on his side – to fellow musician Clarence Carter followed, along with another child, and Staton’s ascent began again alongside the legendary producer Rick Hall at Fame studios in Muscle Shoals. Grammy nods accumulated, but it was with her next collaborator that she would be catapulted into superstardom, with a song that laid bare the horrific abuse she was suffering at home. By then, Staton was signed to Warner Bros and married to the music promoter Jimmy James. She has said in several interviews that James threatened her life. Today she explains that he was “real, real abusive and controlling. He said if I ever divorced him, he would kill my mama, kill my children, kill me, kill us all. [He said] don’t even mention the word divorce.”

Recounting the situation to Crawford, she was unaware that her producer and friend was writing a song about what she was enduring: Young Hearts Run Free. She recorded it in one take. “I listened back to that song and the feeling was there: the intensity, the hurt, the pain,” she says. “It told my life story in three minutes.”

As well as the abuse from James, she was also in the grip of alcohol addiction. It was at a record label party some years earlier that she’d had her first drink of champagne. After a welcome toast, she had continued to drink, “and I started feeling a little more sociable. I wasn’t as nervous, I started smiling and shaking hands. And I took another drink, and another drink …” Soon, she says, “Johnnie Walker was my boyfriend … I would have it in my dressing room, on my rider. I would have it before I went on stage. I couldn’t go to sleep without it, couldn’t wake up without it.” In 1982, Staton – who was no longer with James by this point – says she “decided I didn’t wanna do this any more. My kidneys hurt so bad that I would black out sometimes. I was like: ‘I got to stop.’” Her mother pleaded with her to give up drinking, lest it killed her “like it did your daddy”. Staton went cold turkey, although she doesn’t necessarily endorse the approach, and became a committed Christian (as she remains today), going to church with Chaka Khan’s sister, Taka Boom. Staton retreated from secular music in the 80s, releasing gospel songs and presenting religious TV shows alongside her then husband John Sussewell for the best part of two decades.

All was well, until she and Sussewell divorced in 1998. The Christian music world got word of the split, and the distributor of her upcoming album pulled out, leaving Staton’s career to stall once again. “I started screaming and crying like I’d been beaten,” she says. “I said: ‘God, I don’t have a thing. What are you gonna do?’ I stood up and said: ‘God, anything, any doors that open, I’m walking through them.’” A European tour proved the answer to her prayers, and kickstarted a career resurgence on the other side of the Atlantic. It helped, too, that Staton had just had an unexpected hit in the UK: You Got the Love, originally recorded for a documentary charting one man’s weight loss, was gaining ground as what can only be described as a club banger. Originally remixed over a version of Your Love by Frankie Knuckles, a version by the British group the Source landed the song its highest chart position – No 3 – in the UK in 1997.

Staton wasn’t overly impressed at first, telling the Guardian in 2014 that she had “forgotten about [it] and they’d remixed it to such an extent I wasn’t even familiar with the changes and the chords … I thought: what in the world have they done to this song?” Slowly, though, she warmed to her new hit. It would go on to become an even bigger deal when Florence + the Machine put their indie rock spin on it in 2009 (at the time of writing, that version has been streamed on Spotify more than 687 million times). “[Florence Welch] taped it while I was doing the Glastonbury festival [in 2008],” she explains. “We worked on that arrangement for three days, and she had it on her phone and went in the next week and did [the same one]. I don’t care, because I own half the publishing. So anyway, great Florence – I’m glad you did it. We still make money off of it!”

Now in her 80s, and having been given the all-clear from breast cancer in 2019, you could forgive Staton for slowing down. Instead, Back to My Roots, produced alongside her son Marcus, sees her giving her all on songs such as Peace in the Valley – made popular by Elvis Presley, later a gospel standard – and the Rolling Stones’ Shine a Light.

Of the original tracks, 1963 is the most striking – a rousing spoken-word tribute to the four young girls killed in the racist bombing that took place that year at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in which she also pays tribute to other children killed in tragedies such as the Sandy Hook and Uvalde school shootings. Staton was a young mother at the time of the Birmingham attack, and was in the city with her two eldest sons that day. She adopts the brace position as she demonstrates how they sheltered from the blast, which was orchestrated by local KKK members. She didn’t like the way that the media described the victims – Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Roberston and Denise McNair – as “four little girls; they didn’t name them. They had futures, they had purpose, and it was taken from them. At least call their names. I cried through recording it all. When it was over, my kids were looking at me, saying, ‘Mom, are you OK?’ I said, ‘Not right now, I’m not.’ It was like a grief.” In I’ll Take You There, she walks around the church, quietly taking in the spot where – eerily – only the face of Jesus had been blown out of the stained glass by the bomb.

It’s hard to believe that so much has changed – and that so much has grimly remained the same – in Staton’s lifetime. While Beyoncé was arguably snubbed by the CMA awards for her Cowboy Carter album, black artists are certainly more prominent in Americana and country now. How does it feel for Staton to get more recognition in an area where black artists haven’t always got their dues? “Timing is everything,” she says. “They were not ready to accept us. Now the music industry has changed so much … back then, Rick Hall had confidence in me, but promotion and radio were not ready for me to sing [Jolene] because it was considered white music.” As for newer artists, she says that it feels “great” to see them embrace Americana, and shake it up. “I think it’s about time,” she adds. If anyone knows about the importance of timing, it is Candi Staton.

Candi Staton’s new album, Back to My Roots, is out 14 February on Beracah Records.

Source: theguardian.com