The bookshop in the town where I used to live had a world-beating second-hand selection. The music section alone was so bounteous that there was a second shelf dedicated solely to books about Bob Dylan. One of them provided an inadvertent punchline to the six-foot display, proclaiming: Why Dylan Matters. Thank god, someone said it!

I have cared about music for about 30 years and been a working music journalist for more than half of that time. You can’t avoid the fact that Dylan matters, yet I had always remained Dylan-agnostic. No one in my family is a fan. I saw I’m Not There when it came out, aged 18, and didn’t really get it. On an interminable van journey from Cornwall to Edinburgh, friends played a CD of his greatest hits, but it left no lasting impression. As a teenager I found his music sounded dusty in the way that old records often do when you’re revelling in the newness of your own, formative era.

As I got older, I figured Dylan’s music would always be there waiting for me – perhaps a listening project for when I turned 40, or 50 – and that the well-tended field of Dylanology filling that secondhand shelf would fare quite alright without me. At my most cynical, I resented the weight of Dylan’s legacy. Once, when doing some freelance shifts at Uncut magazine – like Mojo, a publication essentially built in Dylan’s image – I wrote up news on the latest edition of The Basement Tapes and asked whether anyone would truly be excited about these studio dregs. The desk erupted: “Judas!” (That much, I know.)

And then I saw A Complete Unknown. I went out of professional duty and there not being much else to do in January. Some friends refused to see it, assuming it would be some kind of sacrilegious affront. With no skin in the game, I didn’t care either way. But I left the cinema fizzing with teenage-worthy obsession. I’ve scarcely listened to any other music since. I’ve watched Dont Look Back and have a date planned with No Direction Home. I have volume one of Dylan’s memoirs cued up as my next read. I’m ready for the weird Christian albums.

It feels silly, almost girlishly juvenile, that a major Hollywood movie starring a well-studied heartthrob has done for a woman of 36 what the Dylan industrial complex – the magazines, books, reissues and Nobel and Pulitzer prizes – did not (though the many memes suggest I am not alone). I feel so besotted and ravenous for more that it’s hard to break the feeling down to understand it. The New Yorker writer Tad Friend once said that the purpose of the celebrity profile is to properly convey the effect a star has on us. A Complete Unknown may play hard and fast with accuracy, but director James Mangold and leading man Timothée Chalamet comprehensively assert the magic of the young Dylan, as perhaps best summarised in this piercingly accurate review on Letterboxd:

Women: ‘You’re such an asshole. How do you make such good music?!’

Bob Dylan: *unintelligible mumbling*

Women: ‘Fuck, you’re so hot’

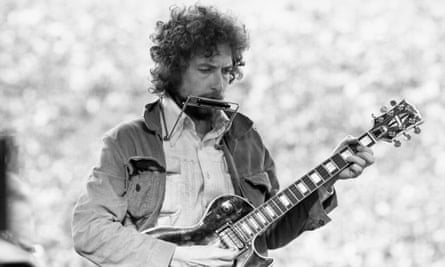

Sidestepping the very real possibility that I may just have developed a massive crush on Chalamet/Dylan/both, perhaps the deeper part of the magic is the air of mystery that Dylan – fictionalised and real; the fictionalised real – exudes. Today, musicians are more or less expected to bare all and to maintain a coherent identity and personal politics, or they risk being accused of inauthenticity or inconsistency. Dylan is all questions, no explanations; tricksy, and funny. Sometimes wise, sometimes a massive dickhead, somehow he always gets away with both. (I loved every sly dig at Donovan in Dont Look Back.) Maybe no one has ever worn sunglasses better.

In A Complete Unknown, Dylan’s antipathy towards stardom rings more contemporary, but the way he toys with it feels more fun and artful than is possible for pop stars in the same position today, bound by a demanding industry and demanding fans. His elusiveness creates a hunger to get closer; more so because you know that with Dylan, you never can, making the potential terms of engagement feel infinite. Meanwhile the women in the film, Joan Baez and a stand-in for Suze Rotolo, feel undersold, and I want to learn their stories on their own terms.

This would all be academic if it weren’t for the songs. The songs! I have nothing new or insightful to tell you about anything on Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde or Blood on the Tracks, my current starter pack, and won’t insult anyone’s intelligence to pretend that I do. I’m just rapt by music that’s almost 60 years old; that once sounded inaccessibly remote and superannuated to me, and now hits like a wave to the face. I can see why critics would write six feet’s worth of books about his phrasing alone. My current favourite is the untouchable hauteur of Blood on the Tracks. The gall of Idiot Wind almost makes me wish I had an ex bad enough to sing it to, although the concluding shift from the indicting “you” to “We’re idiots, babe / It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves” guts the song’s bellyful of contempt and takes my breath away.

Maybe a sense of loss contributes towards Dylan’s allure for me too. In A Complete Unknown, his songs catalyse sweeping social change and inspire a generation to break from cultural conservatism – that has never felt more like a fantasy than it does now. One scene in Dont Look Back shows young British Dylan fans awaiting him at the airport. When he appears, their happy screams sound like the ecstasy of kids at a birthday party surprised by a particularly big cake, shrill with an innocence that has since been crushed by the posturing warfare of much contemporary fandom. I’ve just tipped into the second half of my thirties and have been doing this a long time: perhaps the past holds more surprises, now, than the carousel I’ve watched go around and around several times.

In her Pitchfork review of A Complete Unknown’s soundtrack – featuring songs by Dylan, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger, sung by the actors portraying them – critic and Dylan obsessive Jenn Pelly wrote: “One of the joys of Chalamet’s performances is hearing the dizzying, transformative charge of getting into Dylan for the first time – as did Chalamet, who grew up on the work of Kid Cudi and Lil B.” The clear zeal in the 29-year-old actor’s performance made Dylan feel accessible to me – and surely many others – in a way that an overwhelming availability of information didn’t. What a delight, for his enthusiasm to in turn create Dylan converts, whether early in their music fandom or decades into it. Either way, right on time. I must wrap this up as I have six decades of Dylan to catch up on: I’m entering my Basement Snapes era.

Laura Snapes is the Guardian’s deputy music editor

Source: theguardian.com